Just Like Us: a review

Author ········· Sheyma Buali

Published ······ Issue 02, Summer 2011

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Issue 02, Summer 2011

Section ······· Culture

Published in Kalimat, Issue 02, Summer 2011 (read this issue)

Pitch: Just Like Us, a new documentary by Egyptian-American comedian Ahmed Ahmed, was screened during the London International Documentary Festival. The film, although attempting to bridge cultures, prolongs the question of Arabs' cultural isolation at a time when Arab cultural inclusion is at its strongest.

Going to see Egyptian-American comedian Ahmed Ahmed’s new documentary, Just Like Us, it must be said that from the get go, there was scepticism. The premise of the film asks: do Muslims and Arabs laugh? To which the answer would be, yes they laugh Just Like Us. The film attempts to bridge cultures by following Ahmed and his group of ethnically mixed Western comedians on what was truly a very funny stand-up tour in the Middle East. But despite the comics’ stand up skill, the premise of the documentary remains an awkward one, prolonging the question of Arab cultural isolation.

The film takes its audience to four very different Arab countries: (Dubai) United Arab Emirates, (Beirut) Lebanon, (Cairo/Alexandria) Egypt and (Riyadh) Saudi Arabia. The documentary includes clips from live stand-up by Ahmed himself and the different members of the troop. Taboo jokes about whether or not men should scream during sex were told by lone-female comedienne Whitney Cummings while Omid Jalali’s faux-pas use of the word “cock” in front of a supposedly conservative Dubai audience pushed the envelope of what is permissible in live performance there. Maz Jobrani’s inspection of local greeting styles added cultural fish-out-of water humour. Cutaways of confused hello-kisses with men in thobes created a hilarious cross over from stand-up stage to movie screen. In other parts, the documentary follows Ahmed as he reconnects with his native neighbourhood in Alexandria where his semi-estranged family lives, clueing us in that this films stands as self-reflection as much as a cultural exploration. His father, at home in the United States (US), nearly steals the show, telling endearing jokes with that familiar fatherly not-that-funniness giving the documentary its warm edge.

But despite the laugh-with-tears reaction, the premise of the documentary isolates the Arab world’s culture and humour uncomfortably. Contrary to that (and arguably equally as questionable) the last few years’ focus on the Arab world and its culture has been stronger than ever. Last month’s glitzy global Cannes Film Festival decided on a new feature: an annual national focus. For this inaugural year, they chose Egypt. In London, the London International Documentary Festival (where Just Like Us screened twice) had a focus on the Arab world. In the US for the next two months, conscious of the vilification of Arabs’ image, Turner Classic Movies will be focusing on Arabs in cinema with the scholar of that very topic, Dr. Jack Shaheen.

Globally speaking, at this point of Arab cultural inspection, post-post-9/11, post-Osama Bin Laden and so on, the question of de-demonising Arabs by showcasing how “they” live is, to put it simply, passé. Attempting to explore how (or whether) people in the Arab world laugh, Just Like Us excludes Arabs from a universal human element, extending the crass ‘us versus them’ mentality.

At one point in the documentary, Tommy Davidson, one of the comedians who joined Ahmed’s troop in Beirut remarks that people in “this area are just learning how to laugh because of the intensity of their reality.” In another clip, Omid Djalali explains, “we don’t know the basic construct of a joke.” It is these remarks that insist on the separation of Arabs (and, once again, Muslims) from “us” (Westerners) by referring to them with such a cold, distant and systematic lens. As noted by anthropologist Mahadev Apte, humour and language go together as basics of human expression and communication. Palestinian writer Ibrahim Muhawi explains further the universal “techniques” of humour (such as “mimicry, exaggeration, mockery and nicknaming.”) This obvious human commonality is what makes the interpolative basis of this film borderline offensive.

Bringing this question to the visual element, this insensitivity is displayed in the unfortunate graphics. In standard Orientalist fashion, the typeface for both the titles throughout the documentary and its PR material mimics a Sanskrit design. This visual mish-mash alluding to the relatively close Indo-Aryan-Arab regions fits the precise definition of what is considered “Orientalist”, in the Said-ian fashion, generalising an unknowing idea of what is “Eastern”. The irony however, is that among the opening jokes of the film, Ahmed talks about how many people have responded to him being Arab by saying, “I have a friend from India”, the punch line being the insignificance of that reference. In answering a question about the humour of Arabs and Muslims (quite general in themselves) the visual elements only confuse this regional/cultural obscurity even more; more or less, the graphics work against the desired ultimate message of the documentary.

The film could be divided into three sub-stories. The comical documentary that follows North American comedians in the Arab world; the warm familial background that made the film personal to Ahmed; and that hapless interpolative question that instigated the film. As Just Like Us illustrates, Ahmed Ahmed and his first comedy troop, the Axis of Evil, sparked a stand-up craze in the Middle East about five years ago. Ahmed is a funny guy, and there is no doubt that he has brought something fresh to the Middle East with his culture-bridging entertainment, in both his stand up and his films. If only he would let that shine instead of burying it in dead questions.

Pitch: Just Like Us, a new documentary by Egyptian-American comedian Ahmed Ahmed, was screened during the London International Documentary Festival. The film, although attempting to bridge cultures, prolongs the question of Arabs' cultural isolation at a time when Arab cultural inclusion is at its strongest.

Going to see Egyptian-American comedian Ahmed Ahmed’s new documentary, Just Like Us, it must be said that from the get go, there was scepticism. The premise of the film asks: do Muslims and Arabs laugh? To which the answer would be, yes they laugh Just Like Us. The film attempts to bridge cultures by following Ahmed and his group of ethnically mixed Western comedians on what was truly a very funny stand-up tour in the Middle East. But despite the comics’ stand up skill, the premise of the documentary remains an awkward one, prolonging the question of Arab cultural isolation.

The film takes its audience to four very different Arab countries: (Dubai) United Arab Emirates, (Beirut) Lebanon, (Cairo/Alexandria) Egypt and (Riyadh) Saudi Arabia. The documentary includes clips from live stand-up by Ahmed himself and the different members of the troop. Taboo jokes about whether or not men should scream during sex were told by lone-female comedienne Whitney Cummings while Omid Jalali’s faux-pas use of the word “cock” in front of a supposedly conservative Dubai audience pushed the envelope of what is permissible in live performance there. Maz Jobrani’s inspection of local greeting styles added cultural fish-out-of water humour. Cutaways of confused hello-kisses with men in thobes created a hilarious cross over from stand-up stage to movie screen. In other parts, the documentary follows Ahmed as he reconnects with his native neighbourhood in Alexandria where his semi-estranged family lives, clueing us in that this films stands as self-reflection as much as a cultural exploration. His father, at home in the United States (US), nearly steals the show, telling endearing jokes with that familiar fatherly not-that-funniness giving the documentary its warm edge.

But despite the laugh-with-tears reaction, the premise of the documentary isolates the Arab world’s culture and humour uncomfortably. Contrary to that (and arguably equally as questionable) the last few years’ focus on the Arab world and its culture has been stronger than ever. Last month’s glitzy global Cannes Film Festival decided on a new feature: an annual national focus. For this inaugural year, they chose Egypt. In London, the London International Documentary Festival (where Just Like Us screened twice) had a focus on the Arab world. In the US for the next two months, conscious of the vilification of Arabs’ image, Turner Classic Movies will be focusing on Arabs in cinema with the scholar of that very topic, Dr. Jack Shaheen.

Globally speaking, at this point of Arab cultural inspection, post-post-9/11, post-Osama Bin Laden and so on, the question of de-demonising Arabs by showcasing how “they” live is, to put it simply, passé. Attempting to explore how (or whether) people in the Arab world laugh, Just Like Us excludes Arabs from a universal human element, extending the crass ‘us versus them’ mentality.

At one point in the documentary, Tommy Davidson, one of the comedians who joined Ahmed’s troop in Beirut remarks that people in “this area are just learning how to laugh because of the intensity of their reality.” In another clip, Omid Djalali explains, “we don’t know the basic construct of a joke.” It is these remarks that insist on the separation of Arabs (and, once again, Muslims) from “us” (Westerners) by referring to them with such a cold, distant and systematic lens. As noted by anthropologist Mahadev Apte, humour and language go together as basics of human expression and communication. Palestinian writer Ibrahim Muhawi explains further the universal “techniques” of humour (such as “mimicry, exaggeration, mockery and nicknaming.”) This obvious human commonality is what makes the interpolative basis of this film borderline offensive.

Bringing this question to the visual element, this insensitivity is displayed in the unfortunate graphics. In standard Orientalist fashion, the typeface for both the titles throughout the documentary and its PR material mimics a Sanskrit design. This visual mish-mash alluding to the relatively close Indo-Aryan-Arab regions fits the precise definition of what is considered “Orientalist”, in the Said-ian fashion, generalising an unknowing idea of what is “Eastern”. The irony however, is that among the opening jokes of the film, Ahmed talks about how many people have responded to him being Arab by saying, “I have a friend from India”, the punch line being the insignificance of that reference. In answering a question about the humour of Arabs and Muslims (quite general in themselves) the visual elements only confuse this regional/cultural obscurity even more; more or less, the graphics work against the desired ultimate message of the documentary.

The film could be divided into three sub-stories. The comical documentary that follows North American comedians in the Arab world; the warm familial background that made the film personal to Ahmed; and that hapless interpolative question that instigated the film. As Just Like Us illustrates, Ahmed Ahmed and his first comedy troop, the Axis of Evil, sparked a stand-up craze in the Middle East about five years ago. Ahmed is a funny guy, and there is no doubt that he has brought something fresh to the Middle East with his culture-bridging entertainment, in both his stand up and his films. If only he would let that shine instead of burying it in dead questions.

Sheyma Buali is a writer specialising in visual culture and cinemas from the Middle

East. Her work has been published in Arabic and English in

AsharqAlAwsat, Little White Lies and Ibraaz. She is a programmer and

organiser with the London Palestine Film Festival. Prior to this, Sheyma

worked for 10 years in documentary and TV production in Boston, Los

Angeles, and her native Bahrain.

Don’t Shoot me, I can tell you a Joke: An attempt at reviewing Sayed Kashua’s book Native

Author ········· Anna-Esther Younes

Published ······ Online, June 2016

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, June 2016

Section ······· Culture

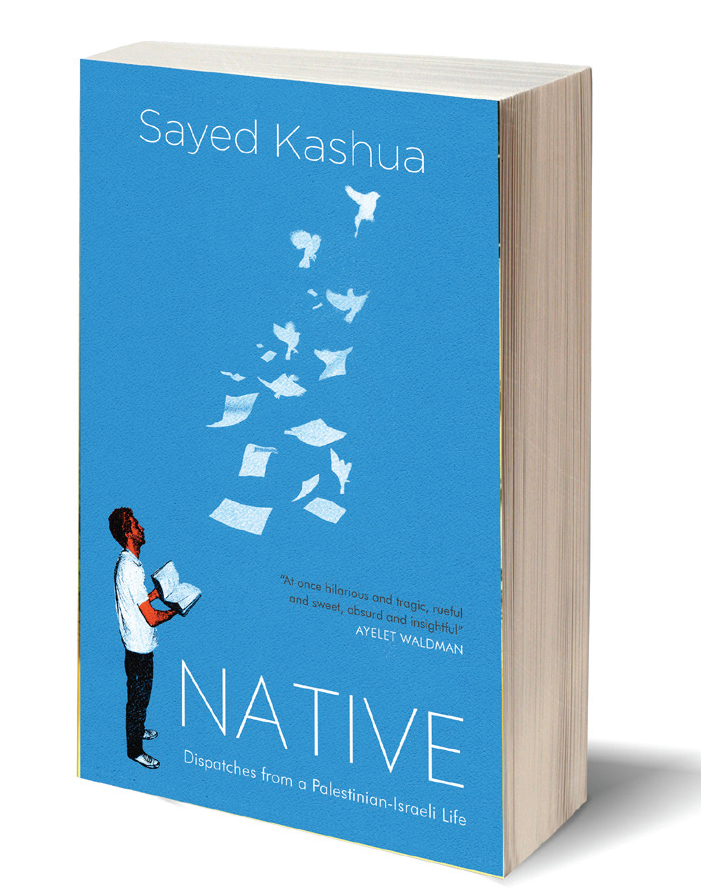

Image courtesy of Saqi Books

Jokes are always contextually situated and have the social function of sharing fantasies, realities and easing pain. They also bind people to each other, and, eclipsed in that function, can also serve to separate people from each other. Sayed Kashua is an example of all of that. Hailed as the hyphenated “Arab” humourist of Israeli society, he is a writer for Ha’aretz, whose weekly satirical columns from 2006-2014 are collected in the book Native – Dispatches from a Palestinian-Israeli Life. Kashua makes many Israelis laugh, but Palestinians don’t always necessarily always join in. What is important and controversial about his work is that he teases out a Palestinian identity for the reader that is inseparable from Israeliness. The everyday-colonialism of an Israeli citizenship is something that is indeed desperately in need of discussing, but most Palestinians are still unwilling to do so publically. For Israelis on the other hand, Kashua thinks that they relish the idea of a Palestinian engaging Jewish Israeli culture. Soberly, he explains in the book, “Everyone wanted to talk about identity, about nationality and foreignness, about detachment, self-determination. They wanted to hear about language, about humour and fears, and the future. And I drank a lot and thought about myself and this thing called a ‘Palestinian citizen of Israel’”.

Whatever side we talk about in this conflict, if we can talk about “sides” at all, all we can say is that humour is universal, but nothing is universally funny. Especially not in Israel and Kashua teases out its limits and possibilities. For instance, the disputed term “normalisation” is unapologetically taken to another interpretative level, when he writes that he turns on the well-known Israeli “Army Radio” in his car, because all other radio stations are playing songs that are too depressing for him. He talks about Palestinian voices that write better in Hebrew than in Arabic and that include the Yiddish nu in their daily vernacular. At the same time, he almost innocently confesses that he has “never been able to distinguish between good and bad, especially in writing”. For many Palestinians outside of Israel some of the issues are still difficult pills to swallow. For many Israeli Jews it appears satisfying to hear Kashua’s accounts in the wake of a power struggle where the recognition of some arbitrarily defined Jewish identity becomes the harbinger of national and political power. For the 48-Palestinians, it might be his very chutzpah that is appealing – of using his Israeli privilege to mirror the existential tit-for-tat of everyday colonialism by telling Israeli Jews “don’t shoot me, I can tell you a joke”.

What is humour in Kashua’s work and to whom is it directed? It seems he is unwilling to engage that question. Kashua rather presents himself as the anti-master of humour, one who never really understands what is going on and hence stumbles into situations that seem to be very ordinary but are strikingly “novel” for him every time. Might it be that the jokes he tells are more about his own (structural) repressions than about a funny situation? Is that why so many Israelis laugh about them? Do some people take the jokes not as an effect of repression, but as an affect of his naivety? Maybe one should write less about Kashua himself and more about how Israeli Jews and Palestinians receive his humour.

Native is built up into four parts where each of them is meant to represent a change in his writing. Usually one has to look for the political developments (including the wars) that accompany the years he is writing in. His silence on national politics seems intended and should thus be read as a political statement in his columns. Except in the last chapter, the one where he prepares to leave Israel, he talks history through personal experiences – the most political thing one could probably do in a settler-colonial state. Until then, however, Kashua deconstructs what a Palestinian, or generally speaking “the Other”, is supposed to be. Instead of writing like the “Other”, he writes like “Them”. There is a certain anxiety around the way he intends to write like those whose privilege grants them respect albeit disinterest, anonymity despite power: Thus, seemingly apolitically and “like everybody else” – aka Israeli Jews – Kashua writes about assembling a shoe-rack, getting drunk with women at Israeli clubs and bars in West Jerusalem, or obsessing over his partners un-/distracted attention, to name just a few examples. He plays with a mixture of surrealism and cynicism, adhering to a simple and successful strategy of feeding offense to those you aim to criticize: only talk about yourself, never about them. Yet, knowing full-well that his mimicry of Israeli Jewish ordinariness is bound to fail, he recurrently reminds the reader of the fantasy the privileged want to believe in: “I’m the kid who made it all the way from Tira [the Palestinian village he is from] to a black executive car. I am the one who will prove to everyone that it’s possible, really possible – you just have to believe”.

Image courtesy of Saqi Books

Kashua’s humour lives from a persona he calls a defeatist, addicted to cigarettes and alcohol. He also seems to think of himself as the embodiment of the system’s joke: a foolish anti-hero, an apathetic coward, one with whom one either feels sympathy or anger, rather than empathy or disgust. His first-person narrative-style lives from notorious lying and a defeatist desire to be like “them”. Kashua is well aware that Israeli Ashkenazi culture and education has suppressed and formed him. Thus, i.e., in his usual self-ridiculing way, he opens the book with a story, which ends by him telling passers-by’s in the Palestinian neighbourhood of Beit Safafa that “he is the only Ashkenazi in the neighbourhood”. He is well aware that the one, who wants to shine on stage, needs to be blinded by the light first.

The way he describes the daily micro-aggressions of colonialism and racism in Israel is simply to crack a joke about its ordinariness. Sometimes his jokes appear to be a survival strategy of someone whose security depends on deception; at other times it appears that his humour is a way of dealing with the anxious energy bound up in the Self, when being a subject at the whims of colonial education and power; yet on other occasions Kashua’s humour also appears as a neurotic character flaw, a “paranoid personality disorder” as his wife attests. Another option might be to think of it as a fusion of all these possibilities, embodying the inevitable characteristics of personal coping mechanisms amidst racism: whilst trying to avoid more pain one refuses the need to investigate its sources. A good example is his unsuccessful attempt to avoid being ushered into the lane for Arabs upon entry at the Tel Aviv airport. After some embarrassing moves to hide something that was never defined by him, he gives in to defeat, gets in line with the other “Arabs” and writes about finally “lowering his head” whilst “trying to be natural” in this.

Kashua chose to move his Palestinian family into an all-Jewish neighbourhood in West Jerusalem. He admits that his anxious integration work is built on the hope that one day his kids will have it better than him and his wife, by wanting them to be like those “white people who, when they grow old complain about the piano lessons they were forced to take.” Then, once his kids made it, he will be satisfied thinking, “They’ll complain about the violin; my daughter will complain about the piano. That’s what I call equal opportunity”. It is hard to escape his sarcasm at times. What is interesting about Kashua is that throughout the years, his identity becomes that of a Person of Colour who, for instance, sees the similarities of being an Arab in France to being an Arab in Israel. He realises that giving one’s geographical address plus an Arab family name when calling the electricity company (or the police, or an internet provider, or the ambulance, for example) actually dictates if help is on the way, or not.

The lesson he draws is that this position in society is not unique to Palestinians, but different. But the way he writes about his occupiers and friends is nevertheless with empathy and understanding even in the face of his own subjugation. In a way, one is reminded of Kafka’s Gregor Samsa (The Metamorphosis), who after turning into an animalistic creature still maintains compassion for his family’s tendency to inquire about “what he is” and “where to put him”, banning him to his room until, as they hope, it’s all over and Gregor will vanish by himself. Seen as an abhorrent creature by the family of man, Kashua and Samsa still have compassion, as long as the Other’s defining gaze is more powerful than one’s own knowledge about what is happening to oneself. However, at the end of the book, Kashua’s compassion and palsy seem to fade more and more and his new desire to move to the USA is expressed by him proclaiming that the only difference between the two countries is that at least in the US, everybody can have a gun.

His complete disillusionment in politics and political correctness reaches a tipping-point in the book, when the weather becomes more important than the national elections. A trope that should sound familiar in times of Trump, a failed Left, and rising fascism in Europe and India. About Israeli society Kashua attests that they “feel persecuted and threatened”, which for him fuels such structures. But apart from that analysis, there is more to Kashua’s depiction of a simple Palestinian trying to get along at the whims of a system that supersedes his own powers and understanding: political systems like the ones just mentioned depend on the characteristics he so favourably delineates in detail and with sarcastic nihilism in his stories. Hailed as exceptional, there is in fact only one thing all over Kashua’s columns, namely that he almost desperately tries to convey his ordinariness and helplessness to his readers. Interestingly, that goes mostly unnoticed in the majority of reviews or public endorsements one can read. Hence, in one story, he recounts being on stage in front of Israeli Jews whilst tragically, yet clearly, realising that “The image of a witty, funny, hurting man faded away and was replaced by a miserable wretch who constantly repeats himself as he attempts to wring laughs and sometimes also a few tears from an audience that mainly pities him.” Reading Kashua is thus also to understand that liberalism and democracy under specific conditions (i.e. colonialism) facilitate dehumanisation, even when one can laugh about the seeming normalcy of the effects of its divide-and-conquer matrix.

In the last chapter, Nakba Day is not another day for a cynical story about another self-delusional attempt to integrate (one’s ego) into Israeli society. Instead, it becomes the day to commemorate his grandfather – who was killed in 1948 – and his late grandmother’s wisdom about the future, past, and present of human life even without speaking Hebrew. During this commemoration, he describes his (new?) revelation, that “a house is never a certainty, and that refugee-hood is a sword hanging over me”. After having ridiculed the possibility of kinship all along, and as a person who is ready “to risk [his] life on the altar of free expression” as he describes, he then goes on to finally touch the last taboo: Sumoud. Sumoud, the Palestinian idea to remain on the land by any means possible, is now called into question by Kashua’s unapologetic yearning to leave Israel. He lost hope.

Kashua is now a teacher in the Jewish Culture and Society programme at the Urbana Champaign-Illinois University, 600 km from privatised Detroit and polluted Flint, and living in a militarised civil society where 310 million guns revolve in a country of 320 million people. After having believed for such a long time that humour and writing could change an oppressive nation, he is frustrated by needing to admit, that he now realises that “power only respects power”.

This collection of Kashua’s short essays is important, not only because the humour he delivers is defined by a satirical self-account of everyday-colonialism that had lost its addressee long before it was written. Kashua’s satire is also important because the reality of Palestinians in Israel that Kashua portrays can tell us a lot about a colonial reality in the midst of an ostensible democracy. And although Kashua’s humour couldn’t save him from the realities of this world nor from disillusionment, it will be interesting to see what he will joke about in his new home – the United States of America – a new colonial state with an ostensible democracy.

Buy Native at Saqi Books

Dr. Anna-Esther Younes finished her PhD in Geneva and is currently based in Berlin. Her work focuses on questions of race/racialisation in Germany and Europe, psychoanalysis and race, colonialism, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and anti-Muslim racism in Germany and Europe. Recently, she published the German country report in the “European Islamophobia Report” in March 2016 and organised the first interdisciplinary and international Palestinian Arts Festival in Berlin (2016).

On the Peripheries of Tahrir: Saeida Rouass’ Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter

Author ········· Sabrien Amrov

Published ······ Online, Feb 2016

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, Feb 2016

Section ······· Culture

I do not claim to be

a spokesperson of my generation. I am not a poster girl of the

revolution, nor its victim. But you should read my story so you can see

the big picture in all its glorious detail. After all, what is a big

picture except a collection of smaller ones? And what is a grand

narrative, except the stitching together of a thousand threads pulled

together to make a tapestry of fantasy.

![]()

Sophia warns us right from the start: her story is an ‘Egyptian cliché.’ A Comparative Literature student, she knows best how monotone stories of emancipation, freedom and rebellion can be. But she still insists that her story of the days leading up to and during the revolution in Egypt must be told. She is right.

The novel Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter by Saeida Rouass is refreshing in that it provides a wider frame and deeper backdrop of what the cameras in Tahrir square failed to capture in the days of the revolution. Through the eyes of Sophia, Rouass explores how the uprising found a place in people's’ everyday lives before and during the Egyptian revolution – from the doorman of Sophia’s apartment building to the taxi drivers re-establishing a road to take people to Tahrir square. The story is a collection of reflections by the main character written in a first-person account. Sophia takes us on the journey of what went through her mind, her family’s mind, her community, and the country’s mind as people were watching a revolution unfold in urban Cairo.

But she also offers strong insight on moments of different types of revolutions: the personal – the revolutions inside the family unit and community. The character tells a compelling narrative of human inconsistency: how minds change constantly and how there is always a battle against what your gut feeling is telling you and what your reality tells you; how moments of great resilience can generate both a great sense of rebellion but also of hopelessness; and how people struggle to define a position.

The novel is friendly in its honesty about these inconsistencies, but, more importantly, it is forgiving of the shortcomings in the relationship between the revolution of the people and the revolution of the self. Sophia was not ready to join the fight with the nation at the start. She wasn't against it, she just didn't know where she stood. She shares doubts about deciding to join or to ignore the calls for uprising: “The guilt you feel from inaction is far greater than the guilt from action.”

As the story progresses, Sophia begins to realise that she is not alone; that these moments of ambiguity are making the people around her rethink their view about patriotism. Sophia looks at her surroundings with a critical eye. She reveals how she began to see her family in different ways. Through her father, Sophia sees that he is also capable of sacrificing the comfort of his life in order to see a better life for others in the country. From her mother, she learns that there are daily revolutions in the life of women: as mothers, as wives, as humans. From her brother, she learns that you can never be too young to have a political position and understand that freedom is worth fighting for. From state media, she learns the relationship of and between people and the news, how we look at the news to dictate how we should feel, or understand political values that shape their mode de vie. Yes, these lessons are romantic in nature, but she doesn't care. She warned the reader at the beginning and so she dives into these descriptions with great confidence.

You can read the innocence of the author throughout the 85-page novel, sometimes romanticising, sometimes trying to be pragmatic, and other times taking a turn at cynicism. What the character demonstrates beautifully is how for some people, the revolution was not about all or nothing. It was about them thinking through everyday matters: How to get to school? How to get electricity again?

The spaces where these questions are tackled change throughout the story. At times, Sophia reflects in her bedroom, then at the dinner table with her parents, then with her doorman in the apartment until the reader is taken to the street of Tahrir Square. She draws an approachable picture of how moments of resistance can be so familiar yet so strange. How was it that while everyone seemed to be fixated on the square and what people who went to the square had to say, so many conversations were generating in the suburban areas of Cairo but no one bothered to capture them?

Underneath these layers of glory, what Rouass does very well is engage in conversations regarding very difficult phenomenon in almost every society. The matter in which she writes about reputations, gossip, expectations, and of course, identity, is done simply and appealingly. The character is able to show how entire bureaucracies of control live in people’s everyday lives; from the taxi driver to the professor. Sophia takes us on an intimate journey between consent and dissent and how much of the in between there is.

The author leaves us with an important point: five years after the making and breaking of the Egyptian revolution, Sophia shows us that those moments of awareness generated much-needed conversations at every level. With so much ink spilled over the ‘Arab Spring’ by political analysts – some suggesting its failure, others gripping on so tightly to the nostalgia of the high felt during these moments of awakening – what Rouass does is move the frame elsewhere. She reminds the reader that when those cameras stop shooting and the square no longer lives in our imaginary as viewers, there are people living just a block away from Tahrir, in urban Cairo, trying to return to life with lessons learned and new political values to preserve their dignity. That is maybe cliché but doesn't make it any less real.

Purchase Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter on Amazon UK or Apple Books/Kobo

Sophia warns us right from the start: her story is an ‘Egyptian cliché.’ A Comparative Literature student, she knows best how monotone stories of emancipation, freedom and rebellion can be. But she still insists that her story of the days leading up to and during the revolution in Egypt must be told. She is right.

The novel Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter by Saeida Rouass is refreshing in that it provides a wider frame and deeper backdrop of what the cameras in Tahrir square failed to capture in the days of the revolution. Through the eyes of Sophia, Rouass explores how the uprising found a place in people's’ everyday lives before and during the Egyptian revolution – from the doorman of Sophia’s apartment building to the taxi drivers re-establishing a road to take people to Tahrir square. The story is a collection of reflections by the main character written in a first-person account. Sophia takes us on the journey of what went through her mind, her family’s mind, her community, and the country’s mind as people were watching a revolution unfold in urban Cairo.

But she also offers strong insight on moments of different types of revolutions: the personal – the revolutions inside the family unit and community. The character tells a compelling narrative of human inconsistency: how minds change constantly and how there is always a battle against what your gut feeling is telling you and what your reality tells you; how moments of great resilience can generate both a great sense of rebellion but also of hopelessness; and how people struggle to define a position.

The novel is friendly in its honesty about these inconsistencies, but, more importantly, it is forgiving of the shortcomings in the relationship between the revolution of the people and the revolution of the self. Sophia was not ready to join the fight with the nation at the start. She wasn't against it, she just didn't know where she stood. She shares doubts about deciding to join or to ignore the calls for uprising: “The guilt you feel from inaction is far greater than the guilt from action.”

As the story progresses, Sophia begins to realise that she is not alone; that these moments of ambiguity are making the people around her rethink their view about patriotism. Sophia looks at her surroundings with a critical eye. She reveals how she began to see her family in different ways. Through her father, Sophia sees that he is also capable of sacrificing the comfort of his life in order to see a better life for others in the country. From her mother, she learns that there are daily revolutions in the life of women: as mothers, as wives, as humans. From her brother, she learns that you can never be too young to have a political position and understand that freedom is worth fighting for. From state media, she learns the relationship of and between people and the news, how we look at the news to dictate how we should feel, or understand political values that shape their mode de vie. Yes, these lessons are romantic in nature, but she doesn't care. She warned the reader at the beginning and so she dives into these descriptions with great confidence.

You can read the innocence of the author throughout the 85-page novel, sometimes romanticising, sometimes trying to be pragmatic, and other times taking a turn at cynicism. What the character demonstrates beautifully is how for some people, the revolution was not about all or nothing. It was about them thinking through everyday matters: How to get to school? How to get electricity again?

The spaces where these questions are tackled change throughout the story. At times, Sophia reflects in her bedroom, then at the dinner table with her parents, then with her doorman in the apartment until the reader is taken to the street of Tahrir Square. She draws an approachable picture of how moments of resistance can be so familiar yet so strange. How was it that while everyone seemed to be fixated on the square and what people who went to the square had to say, so many conversations were generating in the suburban areas of Cairo but no one bothered to capture them?

Underneath these layers of glory, what Rouass does very well is engage in conversations regarding very difficult phenomenon in almost every society. The matter in which she writes about reputations, gossip, expectations, and of course, identity, is done simply and appealingly. The character is able to show how entire bureaucracies of control live in people’s everyday lives; from the taxi driver to the professor. Sophia takes us on an intimate journey between consent and dissent and how much of the in between there is.

The author leaves us with an important point: five years after the making and breaking of the Egyptian revolution, Sophia shows us that those moments of awareness generated much-needed conversations at every level. With so much ink spilled over the ‘Arab Spring’ by political analysts – some suggesting its failure, others gripping on so tightly to the nostalgia of the high felt during these moments of awakening – what Rouass does is move the frame elsewhere. She reminds the reader that when those cameras stop shooting and the square no longer lives in our imaginary as viewers, there are people living just a block away from Tahrir, in urban Cairo, trying to return to life with lessons learned and new political values to preserve their dignity. That is maybe cliché but doesn't make it any less real.

Purchase Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter on Amazon UK or Apple Books/Kobo

Sabrien Amrov is a Palestinian-Canadian policy author based in Istanbul.

Strangers: the Syrian diaspora in 19th century New York

Author ········· Saif Alnuweiri

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Culture

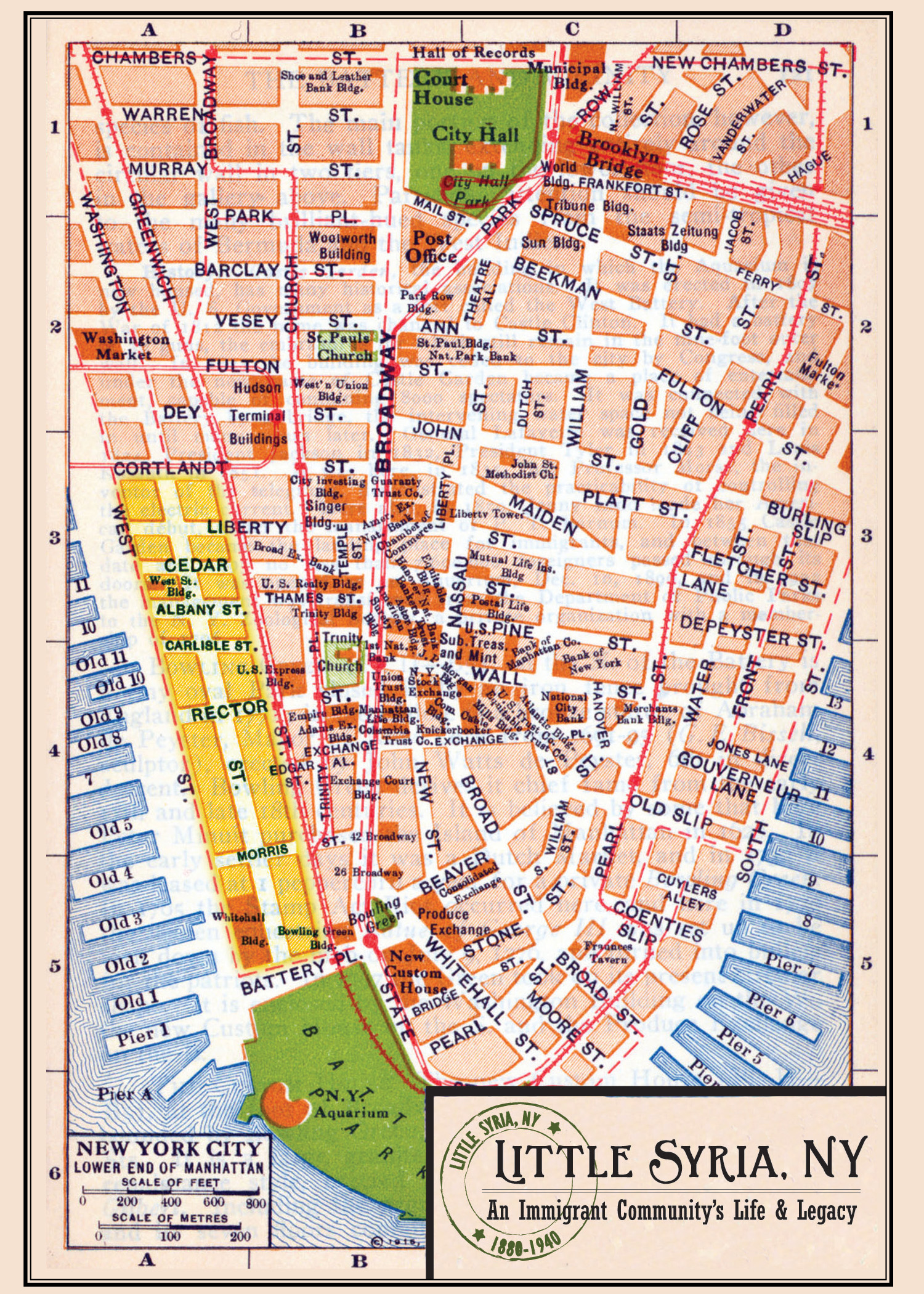

Map showing location of the Syrian colony in Manhattan. Featured is the

postcard from the Arab American National Museum’s original 2012-13

exhibition Little Syria, New York: An Immigrant Community’s Life & Legacy. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

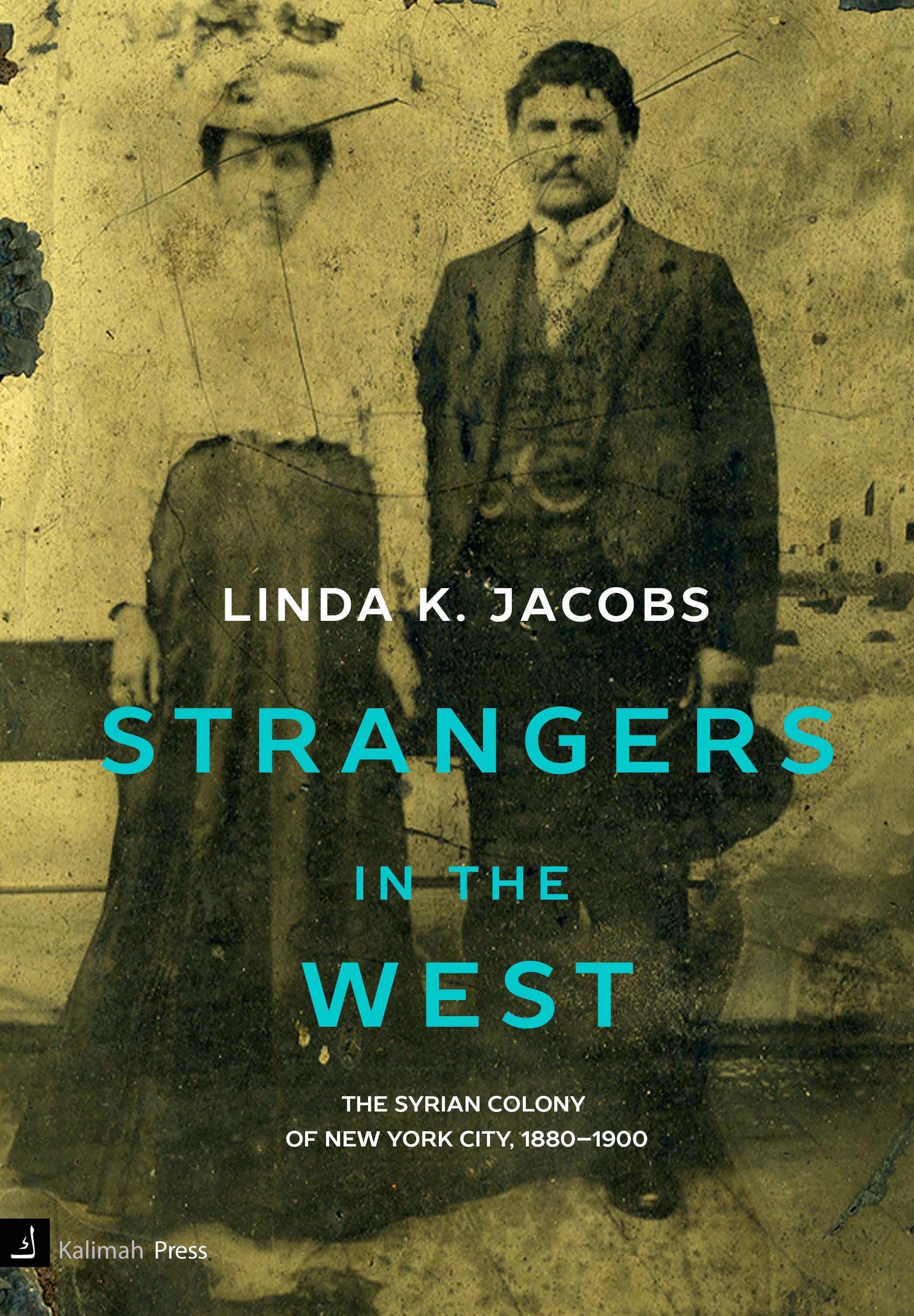

Take a walk along lower Washington Street today and you will find yourself looking up at one of the greatest concentrations of skyscrapers in the United States, one of the preeminent centres of global finance today. A century ago, it was the unlikely location of the largest community of Syrians in the ‘new world,’ as revealed in Linda K. Jacobs recent book Strangers in the West. The book chronicles the history of the community from the arrival of the first immigrants in the 1880s until the turn of the century. It reveals a young Syrian diaspora undergoing the same struggles many immigrant groups in the U.S. faced in the 19th century.

“It was the mother colony of all Syrians in North America,” Jacobs tells me. Her grandparents were both members of the Syrian colony when it was first founded. Educated as an archaeologist, Jacobs started documenting the Syrian diaspora in New York City as a result of an oft-repeated family tale. According to this tale, which Jacobs said was always recounted bitterly by her parents, her grandfather and his two brothers had a falling out over a business they shared in the 1930s. Jacobs decided to check the veracity of the family tale. After having investigated the tale, which turned out to be a conflict over succession more than anything else, she decided to delve deeper into the community her grandparents had inhabited.

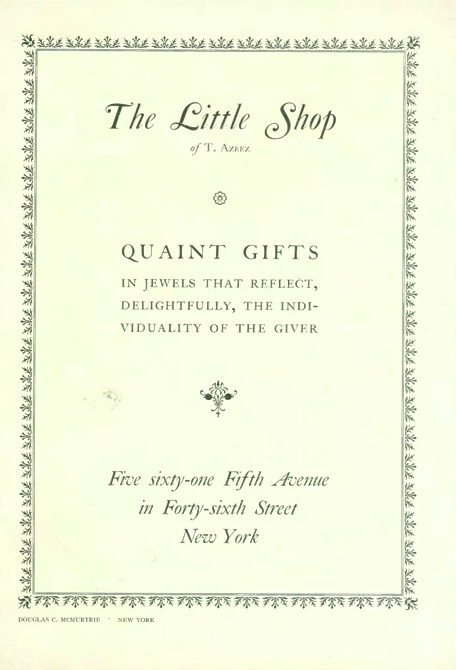

Advert for the Little shop of T. Azeez. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

“It was my mission to reconstruct every Syrian in the colony between 1880-1900 so that they wouldn’t be forgotten,” she says. And she certainly did. Her book is filled with hundreds of Syrians from the colony, some appearing only once in the numerous censuses, databases, and news clippings. Others, like Nageeb Arbeely, appears throughout the book, having been one of two brothers who founded Kawkab America, one of the preeminent Arabic language newspapers that was published in New York during the early colony years. His father, Yusef Arbeely, holds the distinction of being the first recorded Syrian to immigrate to the U.S., although he first settled in Maryville, Tennessee before coming to New York City. While the lists of names and occupations can be exhaustive to read through, they reveal the depth of her three and a half years of research.

29 April 1892 issue of Kawkab America, showing English and Arabic pages. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

In the collective American memory, the struggles of assimilation feature the Italians, the Irish, and the Jews, whose history has been well documented and have been proudly elevated into the pantheon of the “immigrant nation” that America views itself as. However, the Syrian community has not been included. Jacobs says that “it’s partly our fault,” since “we don’t study our own people enough.” It could be because they assimilated so well in their new home. “They were so well assimilated that they disappeared into the fabric of New York City. We were non-threatening and Christian. They had a reputation for being expert assimilators in the countries they moved to,” she continues. The vast majority of immigrants were Christians. There were Maronites, Melkites, Greek Orthodox, and Protestants. Jacobs traced her own lineage back to the Syrian colony in lower Manhattan, where both her maternal and paternal grandparents first lived when they arrived. Her grandparents hold the distinct honour of being one of the few intersect couples of the colony. They later moved to Brooklyn, whose Syrian colony was much more affluent and well established.

Sophie Daoud Shishim, 1895. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Midwife Malakee Nafash, 1908. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Those who left Syria left for a variety of reasons. The oppressiveness of Ottoman rule, which grew worse as the empire grew weaker, made its Christian population look towards immigration to the West. A key factor was the collapse of the silk industry in Syria in the late 19th century. “A lot of people destroyed their crops to plant mulberry trees, so when the industry collapsed they had no money to buy food and no food to eat,” Jacobs tells me. The presence of American missionaries in the Levant also helped towards that end, even if the missionaries were trying to create an educated class that would remain in the region. They had been present in the Arab region since the 1850s, when communal violence between the Druze and Christians spilled over into a brief civil war in the Mount Lebanon area. The crown jewel of their efforts in the region, the Syrian Protestant College, now the American University of Beirut, provided Syrian Christians with the language skills and cultural education to navigate immigrating to the U.S. The Syrian immigrants who arrived on Ellis Island had an easier time with immigration officials if they spoke even broken English.

New immigrants to New York, 1903. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

The few photographs documenting the existence of this community, which stretched from the southern tip of Manhattan up to the Tribeca and Meatpacking districts, reveal a community visibly Arab but also well adapted to Western culture. In one photograph, some dozen young Syrian children are lined up for a group photo on the steps outside a shop, dressed in the same working class outfits that many Italians immigrants, who also immigrated in large numbers at the time, would’ve worn. Their status and their dress reflected their recent arrival to the United States.

Yazaji’s Grocery Store, 1899. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

While they were predominantly Christian, like the majority of immigrants flooding into the country from other parts of the world, they were Arabs. They spoke Arabic. Their shop signs were in Arabic. They had over 40 local newspapers which were printed in Arabic. Some lasted only a couple issues. Others, like Kawkab America and Al-Hoda, lasted decades, and became debating forums for issues all immigrants faced when they came to the U.S. “They were trying to figure out who they wanted to be in the U.S.,” says Jacobs. “There was a debate in the community about how much of their identity they should give up, how much they should sacrifice to become Americans.” The language they spoke however, often misidentified them as Turks, having come from Ottoman provinces in Syria and Palestine.

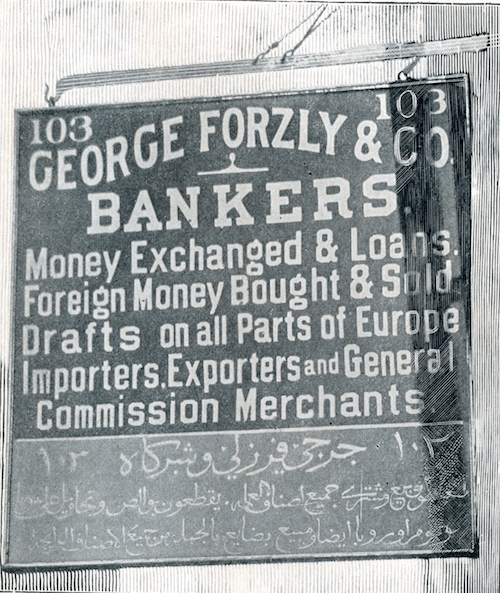

Sign for George Forzly’s Bank at 103 Washington Street, 1897. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Most Syrians started off as peddlers, selling goods not only in Manhattan, but going to resorts in upstate New York. Jacobs’ maternal grandmother and aunt spent the summer of 1907 peddling goods along a string of watering holes as far north as Niagara Falls. Kawkab America reported a Syrian man who walked to Mexico from New York, peddling goods along the way. Jacobs said this was often liberating for Syrians used to the conservative and paternalistic communities that were a fact of life in Syria at the time. It was one of the only ways to advance upwards in society. The New York Herald even devoted a pamphlet to the progression of a Syrian immigrant from peddler to dry goods seller.

25-27 Washington Street, 1897. A double tenement exclusively inhabited by Syrians. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

The Syrians also capitalised on a wave of orientalism sweeping the U.S. in the late 19th century. There were a few pavilions devoted to the Middle East at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. After the fair closed, many of the workers returned home, taking with them tales of their time in America, further heightening Syrian interest in the U.S. By the next major expo, the Syrian were making serious investments. At the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, the Middle East was well represented. In the fairgrounds proper, the Turkish government built its installation, the Turkish Building, and outside of it, there were numerous Arab themed attractions. There was the Algerian and Tunisian Village, the Street in Cairo, the Moorish Palace, the Persian Concession, and the Turkish Village – all built to represent the various peoples of the “Mohammedan World.”

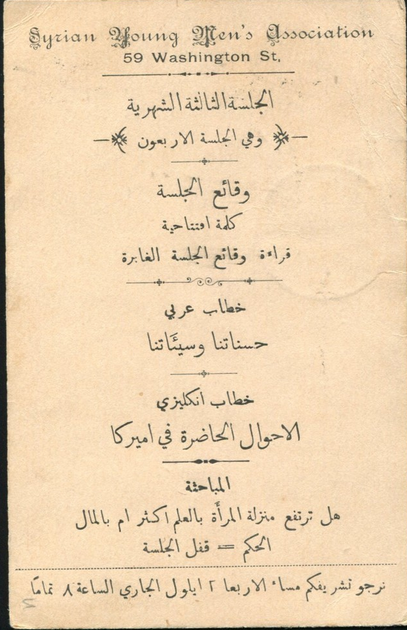

Postcard announcing a meeting of the Syrian Young Men’s Association of New York, 1896. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

What’s most interesting about the early Syrians’ interaction with their new home is the relative lack of animosity they experienced. That is not to say that the process of assimilating into American society was completely prejudice-free, but they weren’t frequent targets of the press. “The newspapers covered the Syrian with a mix of condescension and amusement, “says Jacobs. In the book, she cited a piece published by The New York Evening Post in 1896, describing a Syrian woman as having “a dark olive skin, great black eyes with blackened eyelids, white even teeth, and fine clear-cut features.” An obviously orientalised depiction, it provided insight into the positive exoticism Americans had associated with the new Syrian arrivals.

Various Syrian businesses in New York, 1911. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

But to say the Syrians didn’t experience any hardships would be fallacious, despite the lack of animosity they experienced in comparison to Syrians trying to resettle in the West today. “The only real threat were the street fights with Irish immigrants. The Irish were working down by the docks and the Syrians were self employed, selling Holy Land goods next to them,” Jacobs tells me. “The Syrians reacted angrily but through legal means. They would call the cops, which I found remarkable.” The other major obstacle the Syrians faced was being in a country whose language they didn’t necessarily speak. That was especially an issue given the Immigration Commission’s attempts to impose English literacy tests, which were often circumvented with the help of successful members of the colony, like Kawkab America co-founder Nageeb Arbeely. Jacobs wrote that he would wait at Ellis Island for new Syrian immigrants, whom members of colony needed as a fresh supply of labour for their peddling and shop keeping operations on Washington Street.

Nasri Fuleihan and Isabel Oussani wedding, 1925. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Jacobs’ Strangers in the West is an incredibly well detailed and thoroughly researched compendium on the first recorded Arab community in the U.S. She was able to colourfully reconstruct what it was like to be a Syrian in 19th century New York, at a time when few people imagined there were any Arabic speakers on this side of the Atlantic. And in a very important way, she added Arabs to the immigrant nation narrative that the U.S. prides itself on.

Purchase Strangers in the West

Saif

Alnuweiri is a freelance journalist living in New York and a graduate

of the Columbia School of Journalism. Prior to that he lived in Doha,

Qatar for seven years, where he studied and worked as a journalist

covering local news.

Desert Songs of the Night: 1500 Years of Arabic Literature — Anthology Review

Author ········· Zahra Marwan

Published ······ Online, Sep 2015

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, Sep 2015

Section ······· Culture

“There is perhaps no other literature so closely allied to the history of its people as is that of the Arabs.” Desert Songs of the Night is

a compilation of Arabic literature with stories that vary drastically

from region, time, and theme, and many of which are over a 1,000 years

old. The compilers of this anthology, Suheil Bushrui and James M.

Malarkey, have asked themselves: “how might an acquaintance with Arabic

literature help the reader enter the far more nuanced heart of Arab

experience and aspiration?” The first is to travel, meet people, and

learn how they live their lives in the Middle East. Though, as we are

readily exposed to the region with stories of violence, this path to

learning and of studying the language, culture, religion, and history is

often not considered. The editors have exposed another path to learning

about and understanding the Arabs, and that is through their

literature.

“Poetry, novels, short stories and plays written in Arabic offer a window, as with other literate civilizations, to what many Arabs across the ages have held to be sacred, admirable, noteworthy or scandalous. Few civilizations have invested the word with as much potency and virtue as have the Arabs.” The Arabs refined the art of the written word in order to express themselves throughout the centuries. They used this expression to display their emotional, social, and personal lives. Whereas Europe is known for its well-rendered paintings, the Arab world is known for its literature. The Arabic literature presented in this book deals with subjects that challenged the status of equality between men and women through fiction, whereas some eras elated themselves with honour through poetry. A reader can travel with a youth through his sorrow of leaving his home, and encounter the significance and responsibility of reading and becoming educated which Islam had imposed. Readers who familiarise themselves with this literature will see that they share many common values and aspirations with the ancient and modern writers presented in this anthology.

The pre-Islamic period in the sixth and early seventh centuries was often referred to as the Jahiliyya in Arabic, or “days of ignorance”, and was predominantly tribal. They embodied a heroic ideal through oral poetry. In Al-Khansa's Lament for my Brother, he confronts death, pressuring it to justify itself in not waiting longer in taking the wise. He writes “What have we done to you, death that you treat us so...I would not complain if you were just.” Many of the authors did not hinder themselves in emotional expression. They are more distinct and clear in meaning than they are subtle.

The anthology moves within the historic timeframe, and takes us then to the Islamic period of the tenth century. With the rise of Islam, civilisations in the Middle East were urban, linked through communication lines, and formed around wealth. In the beginning, they were ruled by an orthodox caliphate for 29 years, and were overthrown by the Umayyad family in 661 AD. The Umayyad Dynasty was distinguished for its army and pushing forth of its frontiers. This remains unmasked in their literature, where they amplify science, grammar, and Qur'anic interpretations. Bushrui and Malarkey describe the Umayyad Dynasty's behaviour: “at home there was an increasing tendency to adhere to aristocratic principles; the ruling class paid only lip service to religion and had scant regard for culture. Nevertheless, a number of “sciences” prospered, especially those concerned with elucidation of the Holy Qur’an: theology, history, law and grammar.” In Abd al-Hamid al-Katib's The Art of Secretaryship he recounts the traits of a good craftsman, how to live correctly, and what principles to guide one's life by. Though, parts of it could pertain to our modern day lives:

With the uprise of free thought among the people, in 750 AD, the Shi‘ite and Persian Muslims joined forces under the leadership of the ‘Abbasids to overthrow the Umayyads. The ‘Abbasid dynasty (750- 1258 AD) was established. It flourished for almost five hundred years, and included the period known as the Golden Age of Islamic culture. The ‘Abbasid capital was based in Baghdad, and was highly linked and influenced by Persia. We see the influence that these civilisations had on one another during this dynasty, most notably in Spain, where the 'Abbasids – under Harun Al-Rashid – built their second capital in Granada.

The anthology wraps up with chapters that move through cultural stagnation, literature in the times of colonial encounters, and the reawakening (Nahda) of the Arab world. The work of these authors deserves to be read. Several of the stories reflect the hospitality, resilience, dilemmas, and struggles of the Arabs. The authors of these texts have been driven by inspiration and the ideas of their time. As I read these stories, I slowly became convinced that knowledge of the history of the Arabs through their literature will give an accurate depiction of their culture. The Desert Songs of the Night is an excellent first step towards that knowledge.

Buy a copy of Desert Songs of the Night: 1500 Years of Arabic Literature

“Poetry, novels, short stories and plays written in Arabic offer a window, as with other literate civilizations, to what many Arabs across the ages have held to be sacred, admirable, noteworthy or scandalous. Few civilizations have invested the word with as much potency and virtue as have the Arabs.” The Arabs refined the art of the written word in order to express themselves throughout the centuries. They used this expression to display their emotional, social, and personal lives. Whereas Europe is known for its well-rendered paintings, the Arab world is known for its literature. The Arabic literature presented in this book deals with subjects that challenged the status of equality between men and women through fiction, whereas some eras elated themselves with honour through poetry. A reader can travel with a youth through his sorrow of leaving his home, and encounter the significance and responsibility of reading and becoming educated which Islam had imposed. Readers who familiarise themselves with this literature will see that they share many common values and aspirations with the ancient and modern writers presented in this anthology.

The pre-Islamic period in the sixth and early seventh centuries was often referred to as the Jahiliyya in Arabic, or “days of ignorance”, and was predominantly tribal. They embodied a heroic ideal through oral poetry. In Al-Khansa's Lament for my Brother, he confronts death, pressuring it to justify itself in not waiting longer in taking the wise. He writes “What have we done to you, death that you treat us so...I would not complain if you were just.” Many of the authors did not hinder themselves in emotional expression. They are more distinct and clear in meaning than they are subtle.

The anthology moves within the historic timeframe, and takes us then to the Islamic period of the tenth century. With the rise of Islam, civilisations in the Middle East were urban, linked through communication lines, and formed around wealth. In the beginning, they were ruled by an orthodox caliphate for 29 years, and were overthrown by the Umayyad family in 661 AD. The Umayyad Dynasty was distinguished for its army and pushing forth of its frontiers. This remains unmasked in their literature, where they amplify science, grammar, and Qur'anic interpretations. Bushrui and Malarkey describe the Umayyad Dynasty's behaviour: “at home there was an increasing tendency to adhere to aristocratic principles; the ruling class paid only lip service to religion and had scant regard for culture. Nevertheless, a number of “sciences” prospered, especially those concerned with elucidation of the Holy Qur’an: theology, history, law and grammar.” In Abd al-Hamid al-Katib's The Art of Secretaryship he recounts the traits of a good craftsman, how to live correctly, and what principles to guide one's life by. Though, parts of it could pertain to our modern day lives:

“[s]tudy the Arabic language, as that will give you a cultivated form of speech. Then, learn to write well, as that will be an ornament to your letters. Transmit poetry and acquaint yourselves with the rare expressions and ideas that poems contain. Acquaint yourselves also with both Arab and non-Arab political events, and with the tales of (both groups) and the biographies describing them, as that will be helpful to you in your endeavors.”

With the uprise of free thought among the people, in 750 AD, the Shi‘ite and Persian Muslims joined forces under the leadership of the ‘Abbasids to overthrow the Umayyads. The ‘Abbasid dynasty (750- 1258 AD) was established. It flourished for almost five hundred years, and included the period known as the Golden Age of Islamic culture. The ‘Abbasid capital was based in Baghdad, and was highly linked and influenced by Persia. We see the influence that these civilisations had on one another during this dynasty, most notably in Spain, where the 'Abbasids – under Harun Al-Rashid – built their second capital in Granada.

The anthology wraps up with chapters that move through cultural stagnation, literature in the times of colonial encounters, and the reawakening (Nahda) of the Arab world. The work of these authors deserves to be read. Several of the stories reflect the hospitality, resilience, dilemmas, and struggles of the Arabs. The authors of these texts have been driven by inspiration and the ideas of their time. As I read these stories, I slowly became convinced that knowledge of the history of the Arabs through their literature will give an accurate depiction of their culture. The Desert Songs of the Night is an excellent first step towards that knowledge.

Buy a copy of Desert Songs of the Night: 1500 Years of Arabic Literature

Zahra Marwan spent the majority of her life learning and growing in Albuquerque, New Mexico, yet is of Persian descent and originally from

Kuwait. She studied visual arts for three years in both Paris and Lyon,

and currently works on various professional illustrative projects. These

days, she studies Flamenco dance along with its social and cultural

implications, and tutors undergraduates at the University of New Mexico

in French, Arabic, and English writing.