Strangers: the Syrian diaspora in 19th century New York

Author ········· Saif Alnuweiri

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Culture

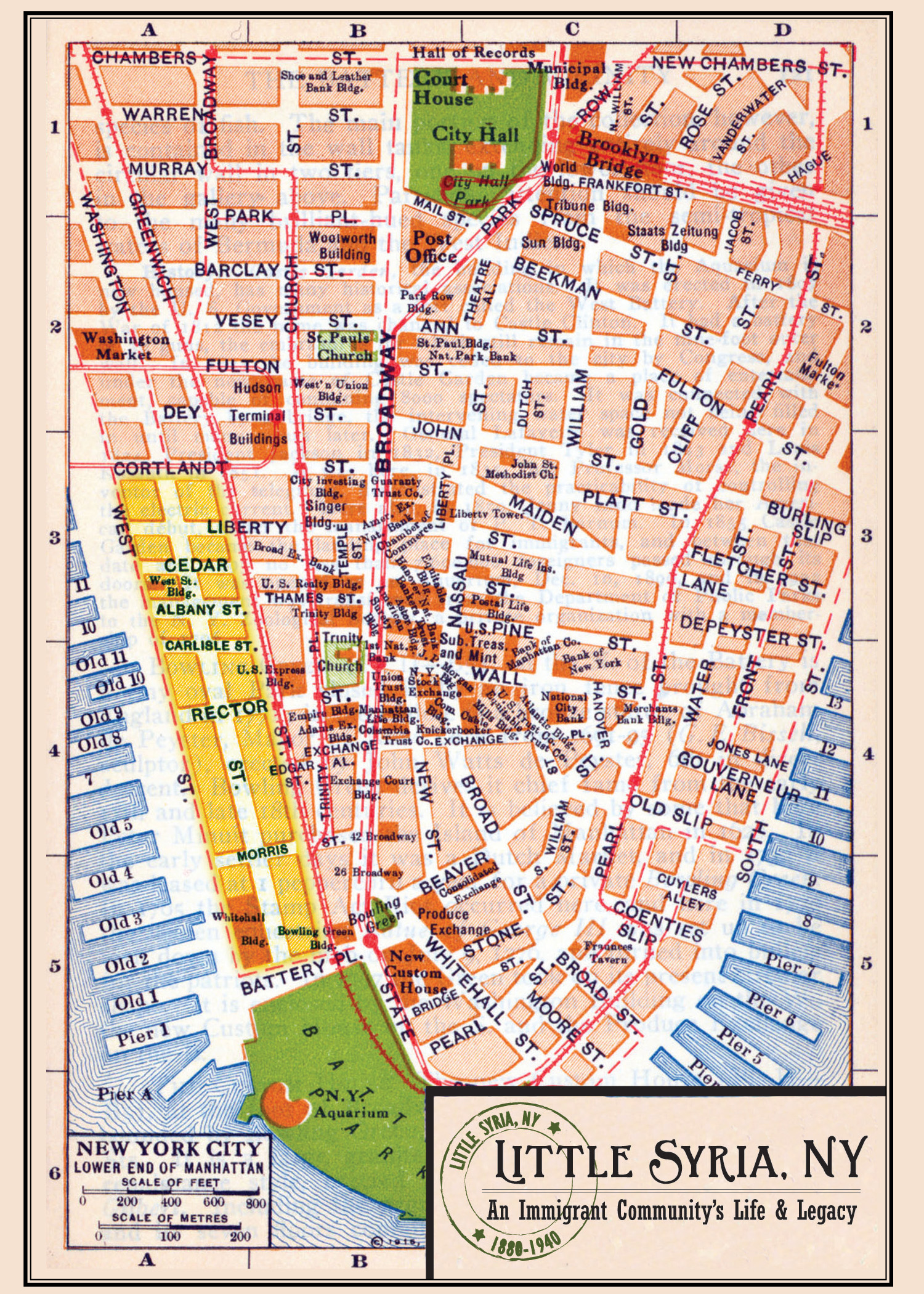

Map showing location of the Syrian colony in Manhattan. Featured is the

postcard from the Arab American National Museum’s original 2012-13

exhibition Little Syria, New York: An Immigrant Community’s Life & Legacy. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

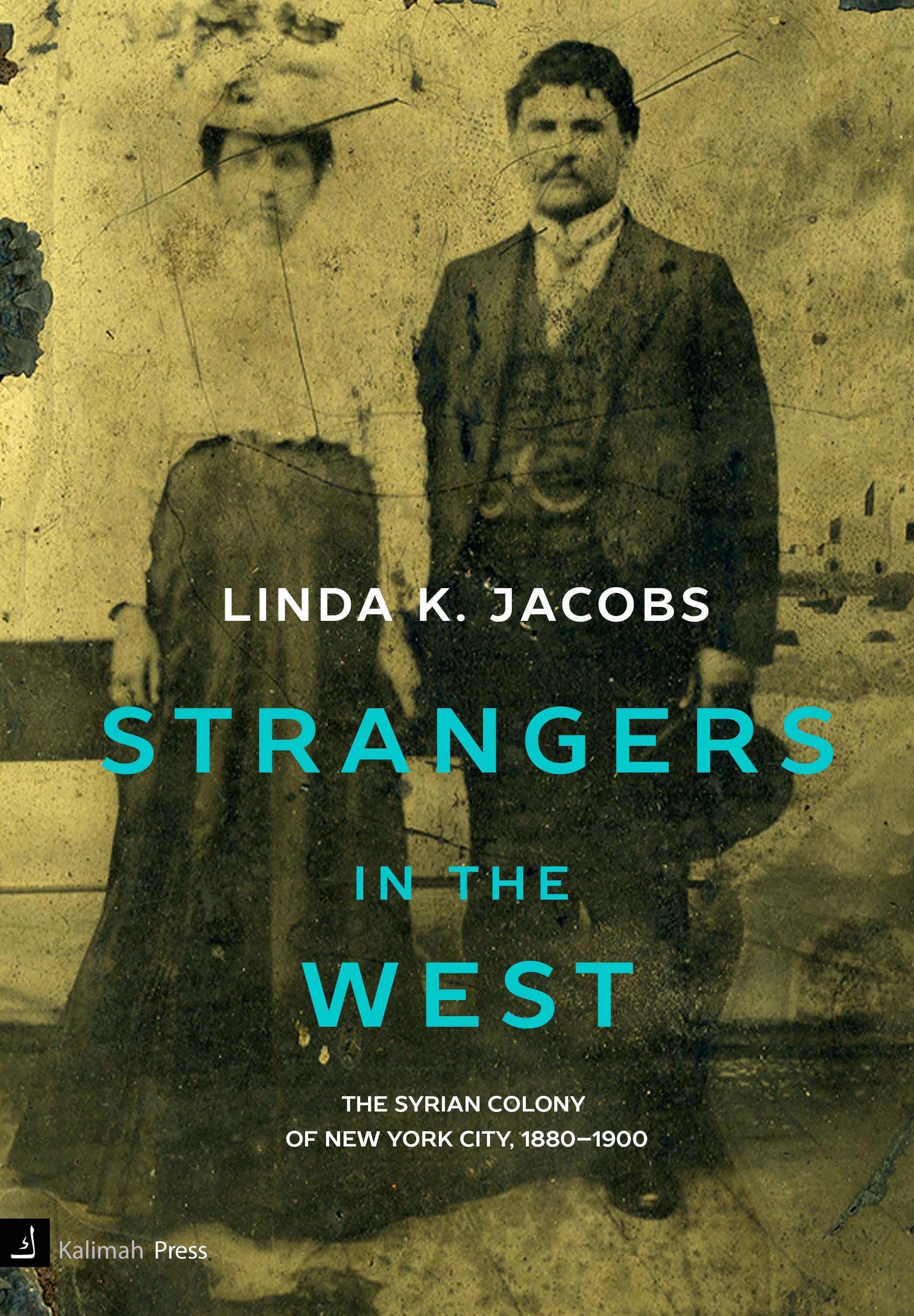

Take a walk along lower Washington Street today and you will find yourself looking up at one of the greatest concentrations of skyscrapers in the United States, one of the preeminent centres of global finance today. A century ago, it was the unlikely location of the largest community of Syrians in the ‘new world,’ as revealed in Linda K. Jacobs recent book Strangers in the West. The book chronicles the history of the community from the arrival of the first immigrants in the 1880s until the turn of the century. It reveals a young Syrian diaspora undergoing the same struggles many immigrant groups in the U.S. faced in the 19th century.

“It was the mother colony of all Syrians in North America,” Jacobs tells me. Her grandparents were both members of the Syrian colony when it was first founded. Educated as an archaeologist, Jacobs started documenting the Syrian diaspora in New York City as a result of an oft-repeated family tale. According to this tale, which Jacobs said was always recounted bitterly by her parents, her grandfather and his two brothers had a falling out over a business they shared in the 1930s. Jacobs decided to check the veracity of the family tale. After having investigated the tale, which turned out to be a conflict over succession more than anything else, she decided to delve deeper into the community her grandparents had inhabited.

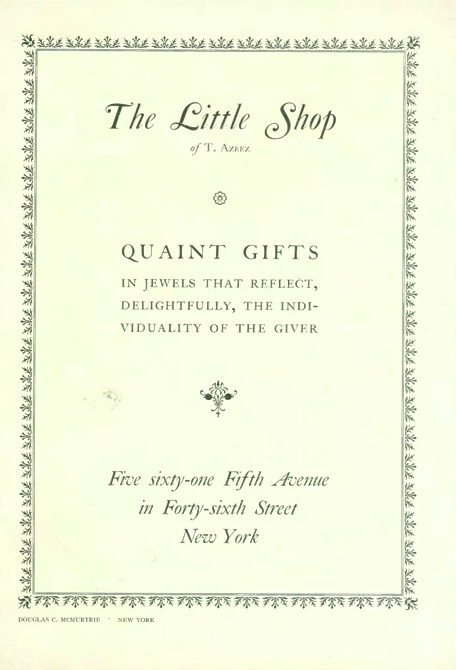

Advert for the Little shop of T. Azeez. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

“It was my mission to reconstruct every Syrian in the colony between 1880-1900 so that they wouldn’t be forgotten,” she says. And she certainly did. Her book is filled with hundreds of Syrians from the colony, some appearing only once in the numerous censuses, databases, and news clippings. Others, like Nageeb Arbeely, appears throughout the book, having been one of two brothers who founded Kawkab America, one of the preeminent Arabic language newspapers that was published in New York during the early colony years. His father, Yusef Arbeely, holds the distinction of being the first recorded Syrian to immigrate to the U.S., although he first settled in Maryville, Tennessee before coming to New York City. While the lists of names and occupations can be exhaustive to read through, they reveal the depth of her three and a half years of research.

29 April 1892 issue of Kawkab America, showing English and Arabic pages. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

In the collective American memory, the struggles of assimilation feature the Italians, the Irish, and the Jews, whose history has been well documented and have been proudly elevated into the pantheon of the “immigrant nation” that America views itself as. However, the Syrian community has not been included. Jacobs says that “it’s partly our fault,” since “we don’t study our own people enough.” It could be because they assimilated so well in their new home. “They were so well assimilated that they disappeared into the fabric of New York City. We were non-threatening and Christian. They had a reputation for being expert assimilators in the countries they moved to,” she continues. The vast majority of immigrants were Christians. There were Maronites, Melkites, Greek Orthodox, and Protestants. Jacobs traced her own lineage back to the Syrian colony in lower Manhattan, where both her maternal and paternal grandparents first lived when they arrived. Her grandparents hold the distinct honour of being one of the few intersect couples of the colony. They later moved to Brooklyn, whose Syrian colony was much more affluent and well established.

Sophie Daoud Shishim, 1895. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Midwife Malakee Nafash, 1908. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Those who left Syria left for a variety of reasons. The oppressiveness of Ottoman rule, which grew worse as the empire grew weaker, made its Christian population look towards immigration to the West. A key factor was the collapse of the silk industry in Syria in the late 19th century. “A lot of people destroyed their crops to plant mulberry trees, so when the industry collapsed they had no money to buy food and no food to eat,” Jacobs tells me. The presence of American missionaries in the Levant also helped towards that end, even if the missionaries were trying to create an educated class that would remain in the region. They had been present in the Arab region since the 1850s, when communal violence between the Druze and Christians spilled over into a brief civil war in the Mount Lebanon area. The crown jewel of their efforts in the region, the Syrian Protestant College, now the American University of Beirut, provided Syrian Christians with the language skills and cultural education to navigate immigrating to the U.S. The Syrian immigrants who arrived on Ellis Island had an easier time with immigration officials if they spoke even broken English.

New immigrants to New York, 1903. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

The few photographs documenting the existence of this community, which stretched from the southern tip of Manhattan up to the Tribeca and Meatpacking districts, reveal a community visibly Arab but also well adapted to Western culture. In one photograph, some dozen young Syrian children are lined up for a group photo on the steps outside a shop, dressed in the same working class outfits that many Italians immigrants, who also immigrated in large numbers at the time, would’ve worn. Their status and their dress reflected their recent arrival to the United States.

Yazaji’s Grocery Store, 1899. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

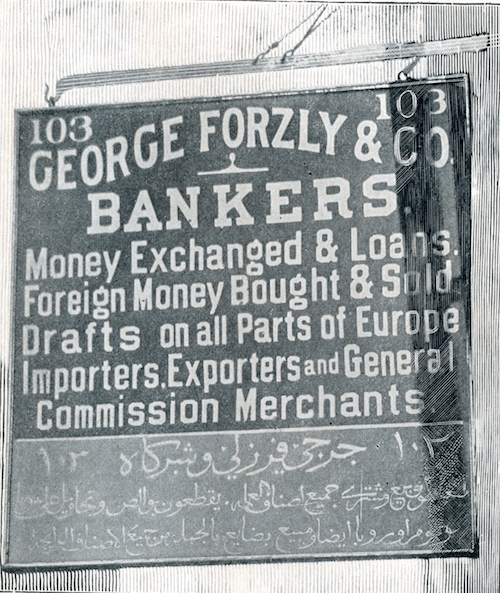

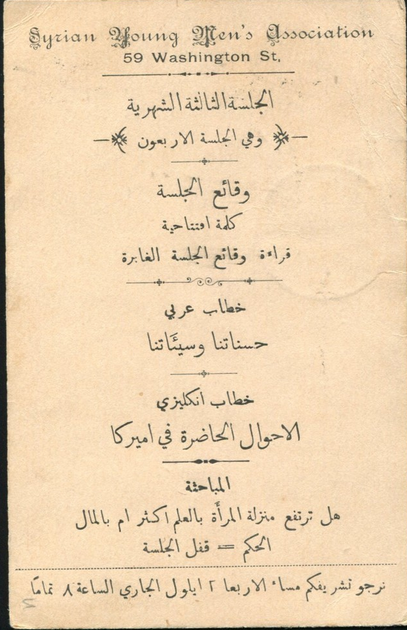

While they were predominantly Christian, like the majority of immigrants flooding into the country from other parts of the world, they were Arabs. They spoke Arabic. Their shop signs were in Arabic. They had over 40 local newspapers which were printed in Arabic. Some lasted only a couple issues. Others, like Kawkab America and Al-Hoda, lasted decades, and became debating forums for issues all immigrants faced when they came to the U.S. “They were trying to figure out who they wanted to be in the U.S.,” says Jacobs. “There was a debate in the community about how much of their identity they should give up, how much they should sacrifice to become Americans.” The language they spoke however, often misidentified them as Turks, having come from Ottoman provinces in Syria and Palestine.

Sign for George Forzly’s Bank at 103 Washington Street, 1897. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Most Syrians started off as peddlers, selling goods not only in Manhattan, but going to resorts in upstate New York. Jacobs’ maternal grandmother and aunt spent the summer of 1907 peddling goods along a string of watering holes as far north as Niagara Falls. Kawkab America reported a Syrian man who walked to Mexico from New York, peddling goods along the way. Jacobs said this was often liberating for Syrians used to the conservative and paternalistic communities that were a fact of life in Syria at the time. It was one of the only ways to advance upwards in society. The New York Herald even devoted a pamphlet to the progression of a Syrian immigrant from peddler to dry goods seller.

25-27 Washington Street, 1897. A double tenement exclusively inhabited by Syrians. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

The Syrians also capitalised on a wave of orientalism sweeping the U.S. in the late 19th century. There were a few pavilions devoted to the Middle East at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. After the fair closed, many of the workers returned home, taking with them tales of their time in America, further heightening Syrian interest in the U.S. By the next major expo, the Syrian were making serious investments. At the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, the Middle East was well represented. In the fairgrounds proper, the Turkish government built its installation, the Turkish Building, and outside of it, there were numerous Arab themed attractions. There was the Algerian and Tunisian Village, the Street in Cairo, the Moorish Palace, the Persian Concession, and the Turkish Village – all built to represent the various peoples of the “Mohammedan World.”

Postcard announcing a meeting of the Syrian Young Men’s Association of New York, 1896. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

What’s most interesting about the early Syrians’ interaction with their new home is the relative lack of animosity they experienced. That is not to say that the process of assimilating into American society was completely prejudice-free, but they weren’t frequent targets of the press. “The newspapers covered the Syrian with a mix of condescension and amusement, “says Jacobs. In the book, she cited a piece published by The New York Evening Post in 1896, describing a Syrian woman as having “a dark olive skin, great black eyes with blackened eyelids, white even teeth, and fine clear-cut features.” An obviously orientalised depiction, it provided insight into the positive exoticism Americans had associated with the new Syrian arrivals.

Various Syrian businesses in New York, 1911. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

But to say the Syrians didn’t experience any hardships would be fallacious, despite the lack of animosity they experienced in comparison to Syrians trying to resettle in the West today. “The only real threat were the street fights with Irish immigrants. The Irish were working down by the docks and the Syrians were self employed, selling Holy Land goods next to them,” Jacobs tells me. “The Syrians reacted angrily but through legal means. They would call the cops, which I found remarkable.” The other major obstacle the Syrians faced was being in a country whose language they didn’t necessarily speak. That was especially an issue given the Immigration Commission’s attempts to impose English literacy tests, which were often circumvented with the help of successful members of the colony, like Kawkab America co-founder Nageeb Arbeely. Jacobs wrote that he would wait at Ellis Island for new Syrian immigrants, whom members of colony needed as a fresh supply of labour for their peddling and shop keeping operations on Washington Street.

Nasri Fuleihan and Isabel Oussani wedding, 1925. Image courtesy of Linda K. Jacobs.

Jacobs’ Strangers in the West is an incredibly well detailed and thoroughly researched compendium on the first recorded Arab community in the U.S. She was able to colourfully reconstruct what it was like to be a Syrian in 19th century New York, at a time when few people imagined there were any Arabic speakers on this side of the Atlantic. And in a very important way, she added Arabs to the immigrant nation narrative that the U.S. prides itself on.

Purchase Strangers in the West

Saif

Alnuweiri is a freelance journalist living in New York and a graduate

of the Columbia School of Journalism. Prior to that he lived in Doha,

Qatar for seven years, where he studied and worked as a journalist

covering local news.