On the Peripheries of Tahrir: Saeida Rouass’ Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter

Author ········· Sabrien Amrov

Published ······ Online, Feb 2016

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, Feb 2016

Section ······· Culture

I do not claim to be

a spokesperson of my generation. I am not a poster girl of the

revolution, nor its victim. But you should read my story so you can see

the big picture in all its glorious detail. After all, what is a big

picture except a collection of smaller ones? And what is a grand

narrative, except the stitching together of a thousand threads pulled

together to make a tapestry of fantasy.

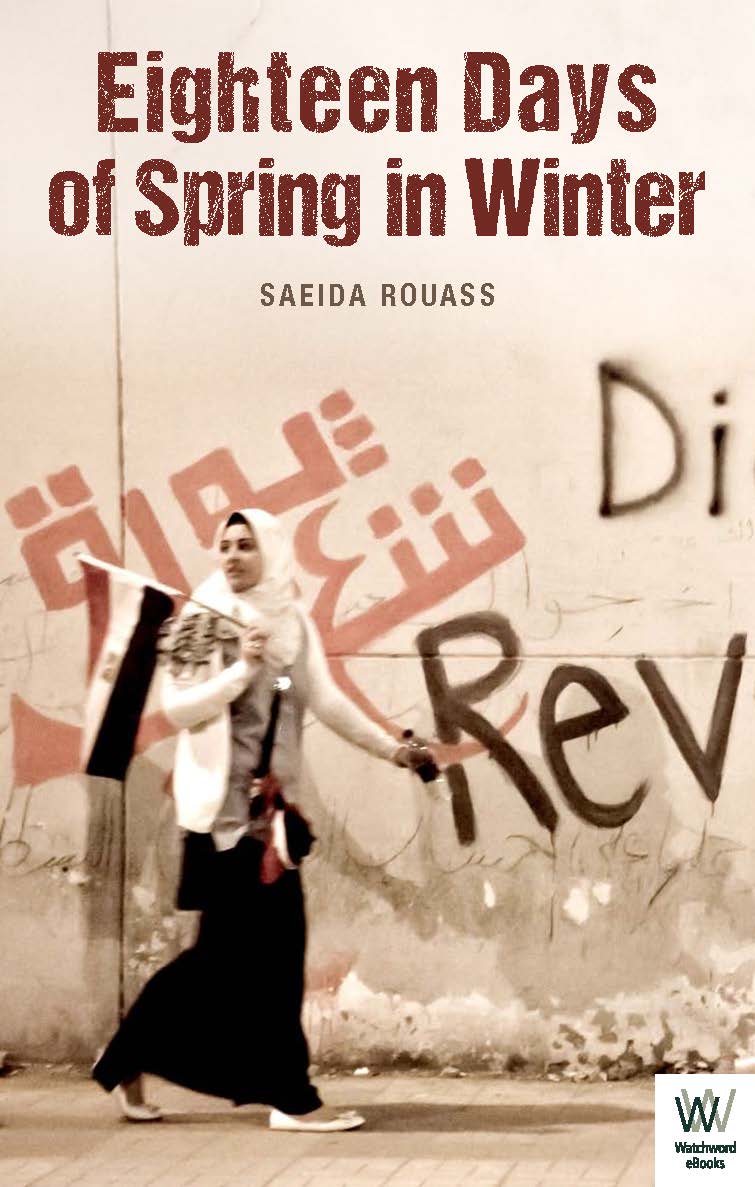

![]()

Sophia warns us right from the start: her story is an ‘Egyptian cliché.’ A Comparative Literature student, she knows best how monotone stories of emancipation, freedom and rebellion can be. But she still insists that her story of the days leading up to and during the revolution in Egypt must be told. She is right.

The novel Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter by Saeida Rouass is refreshing in that it provides a wider frame and deeper backdrop of what the cameras in Tahrir square failed to capture in the days of the revolution. Through the eyes of Sophia, Rouass explores how the uprising found a place in people's’ everyday lives before and during the Egyptian revolution – from the doorman of Sophia’s apartment building to the taxi drivers re-establishing a road to take people to Tahrir square. The story is a collection of reflections by the main character written in a first-person account. Sophia takes us on the journey of what went through her mind, her family’s mind, her community, and the country’s mind as people were watching a revolution unfold in urban Cairo.

But she also offers strong insight on moments of different types of revolutions: the personal – the revolutions inside the family unit and community. The character tells a compelling narrative of human inconsistency: how minds change constantly and how there is always a battle against what your gut feeling is telling you and what your reality tells you; how moments of great resilience can generate both a great sense of rebellion but also of hopelessness; and how people struggle to define a position.

The novel is friendly in its honesty about these inconsistencies, but, more importantly, it is forgiving of the shortcomings in the relationship between the revolution of the people and the revolution of the self. Sophia was not ready to join the fight with the nation at the start. She wasn't against it, she just didn't know where she stood. She shares doubts about deciding to join or to ignore the calls for uprising: “The guilt you feel from inaction is far greater than the guilt from action.”

As the story progresses, Sophia begins to realise that she is not alone; that these moments of ambiguity are making the people around her rethink their view about patriotism. Sophia looks at her surroundings with a critical eye. She reveals how she began to see her family in different ways. Through her father, Sophia sees that he is also capable of sacrificing the comfort of his life in order to see a better life for others in the country. From her mother, she learns that there are daily revolutions in the life of women: as mothers, as wives, as humans. From her brother, she learns that you can never be too young to have a political position and understand that freedom is worth fighting for. From state media, she learns the relationship of and between people and the news, how we look at the news to dictate how we should feel, or understand political values that shape their mode de vie. Yes, these lessons are romantic in nature, but she doesn't care. She warned the reader at the beginning and so she dives into these descriptions with great confidence.

You can read the innocence of the author throughout the 85-page novel, sometimes romanticising, sometimes trying to be pragmatic, and other times taking a turn at cynicism. What the character demonstrates beautifully is how for some people, the revolution was not about all or nothing. It was about them thinking through everyday matters: How to get to school? How to get electricity again?

The spaces where these questions are tackled change throughout the story. At times, Sophia reflects in her bedroom, then at the dinner table with her parents, then with her doorman in the apartment until the reader is taken to the street of Tahrir Square. She draws an approachable picture of how moments of resistance can be so familiar yet so strange. How was it that while everyone seemed to be fixated on the square and what people who went to the square had to say, so many conversations were generating in the suburban areas of Cairo but no one bothered to capture them?

Underneath these layers of glory, what Rouass does very well is engage in conversations regarding very difficult phenomenon in almost every society. The matter in which she writes about reputations, gossip, expectations, and of course, identity, is done simply and appealingly. The character is able to show how entire bureaucracies of control live in people’s everyday lives; from the taxi driver to the professor. Sophia takes us on an intimate journey between consent and dissent and how much of the in between there is.

The author leaves us with an important point: five years after the making and breaking of the Egyptian revolution, Sophia shows us that those moments of awareness generated much-needed conversations at every level. With so much ink spilled over the ‘Arab Spring’ by political analysts – some suggesting its failure, others gripping on so tightly to the nostalgia of the high felt during these moments of awakening – what Rouass does is move the frame elsewhere. She reminds the reader that when those cameras stop shooting and the square no longer lives in our imaginary as viewers, there are people living just a block away from Tahrir, in urban Cairo, trying to return to life with lessons learned and new political values to preserve their dignity. That is maybe cliché but doesn't make it any less real.

Purchase Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter on Amazon UK or Apple Books/Kobo

Sophia warns us right from the start: her story is an ‘Egyptian cliché.’ A Comparative Literature student, she knows best how monotone stories of emancipation, freedom and rebellion can be. But she still insists that her story of the days leading up to and during the revolution in Egypt must be told. She is right.

The novel Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter by Saeida Rouass is refreshing in that it provides a wider frame and deeper backdrop of what the cameras in Tahrir square failed to capture in the days of the revolution. Through the eyes of Sophia, Rouass explores how the uprising found a place in people's’ everyday lives before and during the Egyptian revolution – from the doorman of Sophia’s apartment building to the taxi drivers re-establishing a road to take people to Tahrir square. The story is a collection of reflections by the main character written in a first-person account. Sophia takes us on the journey of what went through her mind, her family’s mind, her community, and the country’s mind as people were watching a revolution unfold in urban Cairo.

But she also offers strong insight on moments of different types of revolutions: the personal – the revolutions inside the family unit and community. The character tells a compelling narrative of human inconsistency: how minds change constantly and how there is always a battle against what your gut feeling is telling you and what your reality tells you; how moments of great resilience can generate both a great sense of rebellion but also of hopelessness; and how people struggle to define a position.

The novel is friendly in its honesty about these inconsistencies, but, more importantly, it is forgiving of the shortcomings in the relationship between the revolution of the people and the revolution of the self. Sophia was not ready to join the fight with the nation at the start. She wasn't against it, she just didn't know where she stood. She shares doubts about deciding to join or to ignore the calls for uprising: “The guilt you feel from inaction is far greater than the guilt from action.”

As the story progresses, Sophia begins to realise that she is not alone; that these moments of ambiguity are making the people around her rethink their view about patriotism. Sophia looks at her surroundings with a critical eye. She reveals how she began to see her family in different ways. Through her father, Sophia sees that he is also capable of sacrificing the comfort of his life in order to see a better life for others in the country. From her mother, she learns that there are daily revolutions in the life of women: as mothers, as wives, as humans. From her brother, she learns that you can never be too young to have a political position and understand that freedom is worth fighting for. From state media, she learns the relationship of and between people and the news, how we look at the news to dictate how we should feel, or understand political values that shape their mode de vie. Yes, these lessons are romantic in nature, but she doesn't care. She warned the reader at the beginning and so she dives into these descriptions with great confidence.

You can read the innocence of the author throughout the 85-page novel, sometimes romanticising, sometimes trying to be pragmatic, and other times taking a turn at cynicism. What the character demonstrates beautifully is how for some people, the revolution was not about all or nothing. It was about them thinking through everyday matters: How to get to school? How to get electricity again?

The spaces where these questions are tackled change throughout the story. At times, Sophia reflects in her bedroom, then at the dinner table with her parents, then with her doorman in the apartment until the reader is taken to the street of Tahrir Square. She draws an approachable picture of how moments of resistance can be so familiar yet so strange. How was it that while everyone seemed to be fixated on the square and what people who went to the square had to say, so many conversations were generating in the suburban areas of Cairo but no one bothered to capture them?

Underneath these layers of glory, what Rouass does very well is engage in conversations regarding very difficult phenomenon in almost every society. The matter in which she writes about reputations, gossip, expectations, and of course, identity, is done simply and appealingly. The character is able to show how entire bureaucracies of control live in people’s everyday lives; from the taxi driver to the professor. Sophia takes us on an intimate journey between consent and dissent and how much of the in between there is.

The author leaves us with an important point: five years after the making and breaking of the Egyptian revolution, Sophia shows us that those moments of awareness generated much-needed conversations at every level. With so much ink spilled over the ‘Arab Spring’ by political analysts – some suggesting its failure, others gripping on so tightly to the nostalgia of the high felt during these moments of awakening – what Rouass does is move the frame elsewhere. She reminds the reader that when those cameras stop shooting and the square no longer lives in our imaginary as viewers, there are people living just a block away from Tahrir, in urban Cairo, trying to return to life with lessons learned and new political values to preserve their dignity. That is maybe cliché but doesn't make it any less real.

Purchase Eighteen Days of Spring in Winter on Amazon UK or Apple Books/Kobo

Sabrien Amrov is a Palestinian-Canadian policy author based in Istanbul.