‘I Say Dust’

Author ········· Wided Khadraoui

Published ······ Online, Jul 2015

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, Jul 2015

Section ······· Culture

Still from ‘I Say Dust’ courtesy of Darine Hotait.

The first shot of 'I Say Dust’ is a tea flower unfurling in a glass tumbler of hot water. The preparation process is part of the integral allure of blooming tea, and also sets the tone of the film. Flowering tea is drunk from glasses so that the action of the hot water uncurling the leaves can be observed. Every thing is up for scrutiny.

The first shot epitomised the film’s beautiful showcase of cinematography, but the narrative and acting is equally as engaging. “What is home?” This question is the centre of the short film ’I Say Dust', written and directed by Darine Hotait. The movie explores the intersection between identity and home. The idea of readapting to a new home and defining identity – sexual in this context – is explored through the two main characters, Moun and Hal, both part of the Arab diaspora in the United States.

In the very short time we spend with them, the difference in self-identity between Moun and Hal – despite ethnic similarities – is critical. They’re vasty different; one relying on the idea of a geographical homeland while the other prefers to have fluid conceptual boundaries of home. The film’s leads showcase the fragile chemistry between social disconnect and psyche that is translated into their love story.

The narrative is beautifully understated, and explores the possibilities inhibited by social conventions, introducing a certain romantic potential while providing almost no concrete explanation for the ebb and flow of the relationship. The ritual of observation initiated by the opening sequence is developed further with shots of Moun and Hal playing chess and of a poetry reading session; stressing the element of monitoring or examining something.

Still from ‘I Say Dust’ courtesy of Darine Hotait.

The story is innovative in that it tackles issues that are usually overlooked in media, mainstream and otherwise, but its main weak point is that the story itself should have been developed on a deeper level. The initial attraction between Moun and Hal is palatable, but the next scene takes us to a more public forum so there was a tangible gap between the development of the romantic relationship. This rift is both a positive and a negative. The audience is allowed to formulate their own narrative, but at the same time, it would have been conducive to have a stronger story line.

The characters are complex, the writing – interspersed with poetry – is so touching, and the shots so poignant it just seems like a damn shame it’s a short rather than a feature length film.

Despite the momentous relationship, the last scene is the most pivotal; with Hal walking by herself in the snow through an eerily silent Brooklyn. The audience understands that the creation for self-identity continues.

Recently, Kalimat had a chance to interview writer/director Darine Hotait about the over lap of sex and identity, the diaspora community, futuristic Beirut, and the importance of dreams in inspiring her work.

Writer/Director Darine Hotait on set. Image courtesy of Darine Hotait.

WK | Having watched ‘I Say Dust’, what initially struck me is that your film cracks the idea of the myth of Arab homogeneity – introducing Arab lesbians who are mitigating that space between identity through sexuality. Where did you get this idea originally?

DH | ’I Say Dust' highlights the topic of Identity in a diaspora context. The idea behind [the film] initially came from my interest in Arab diaspora living in the United States, as I identify myself being part of it. Living in a diaspora often entails having a split and complex identity. I had the idea of two Arab-American women in New York City (NYC), Hal and Moun, who fall in love – a rejected representation of women in the Arab culture – and challenge each other's perspective of what makes home. Now having two Arab women fall in love gave the story a twist that reinforced the theme of identity.

If I was to present a man and a woman, the story's premise wouldn't be as strong and touching simply because this did not break the hailed boundaries. I intentionally wanted to break the homogeneity in the way the identity complex is tackled because I strongly believe that identity is as elastic and resilient as the human's mind and body can be, only if we accept 'the other' unconditionally.

Still from ‘I Say Dust’ courtesy of Darine Hotait.

WK | The intersection between sexuality/love and home is universal, and while this type of love has always been part of the human narrative, why did you choose to portray it through a homosexual lens? Was it a desire to be provocative or just simply universal?

DH | The characters of Moun and Hal are not the typical Arab women characters that we encounter in most movies. Choosing a homosexual angle was something that the story and its theme called for. These two women were able to break the sexual boundaries of their culture. They both live outside of their homeland and they have both adopted elements outside of their culture. In 'I Say Dust' I am questioning what makes home, [and so] it was essential to highlight that home is something that can make us or break us. [This is similar to] love. Love is universal. Love can break us and it can make us. When we experience it, it becomes our identity. The homosexual lens reinforces this idea by introducing the two characters who were able to transcend many cultural boundaries including a sexual one but not the attachment to a homeland. Hal identifies herself by her home country (Palestine) while Moun identifies herself by her love.

WK | Where do you seek inspiration for your stories?

DH | My dreams are my main source of inspiration. I experience very vivid dreams embellished by striking visuals. I often wake up with a story stemming from my own subconscious mind. I also always come back to my personal experiences and what I have lived – when I am ready to face them of course.

Writer/Director Darine Hotait on set. Image courtesy of Darine Hotait.

WK | Tell us more about the process of actualising this story.

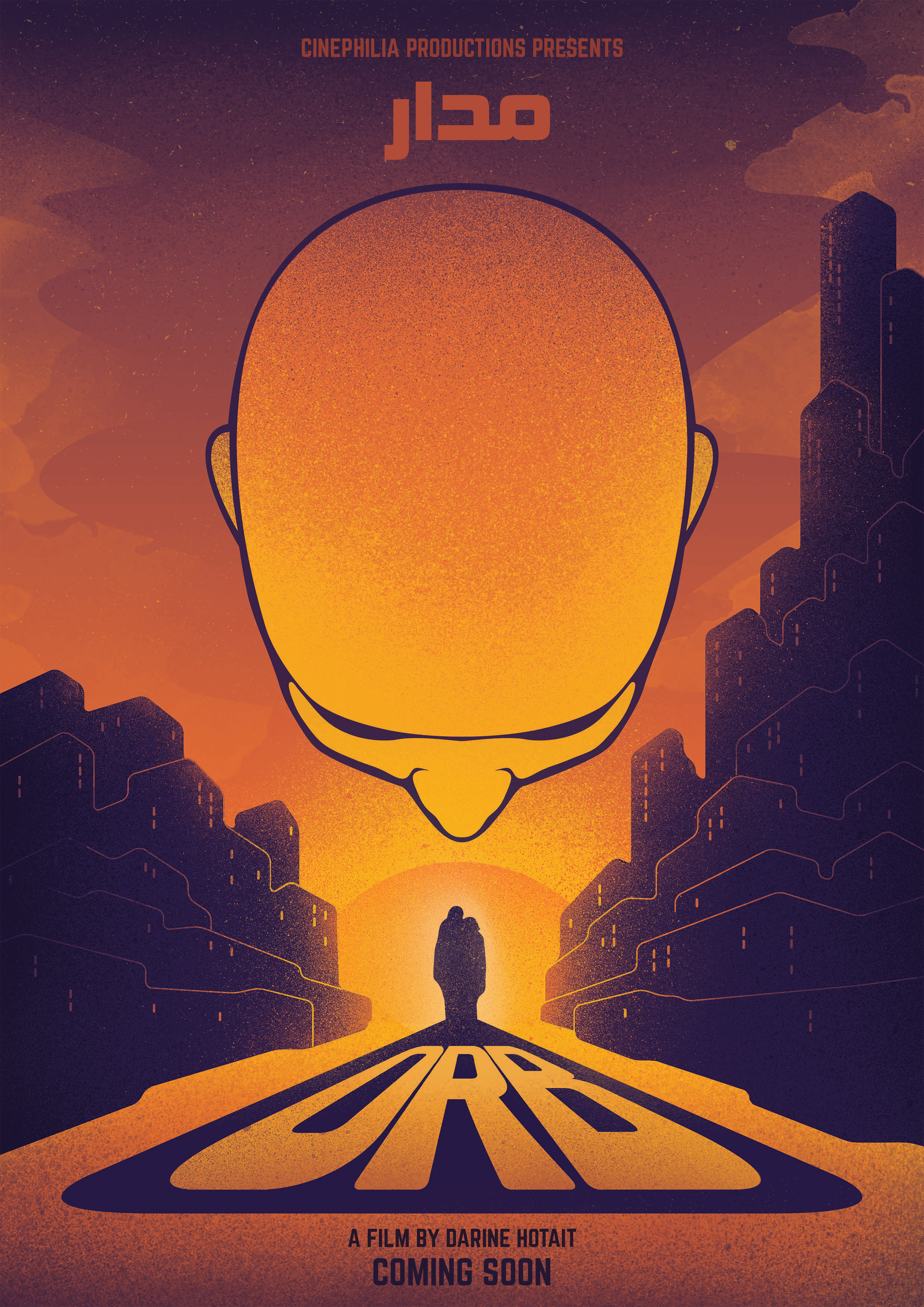

DH | 'I Say Dust' happened naturally and intuitively. I didn't have plans to make it now as I was working on another film called 'ORB' but I just felt the urge to create something. I think I was pregnant with an idea and I needed [to give birth to it]! The storyline [had been] in [my] mind for a while. Then I decided to collaborate with my good friend Palestinian-American poet Hala Alyan by having her play the lead role of Hal (also a Palestinian American poet) and to have her perform one of her poems. This is Hala's first screen appearance. While transforming the story into a screenplay, Hala's poem blended in very nicely as it also talked about identity. It was obvious to me that no one other than Mounia Akl would play the role of Moun; the girl who works in the shop that sells chess sets and offers Hal her first lesson, which sets the whole relationship in motion. Mounia also happens to be a good friend and a very talented actress and film director.

It was the first time I wrote a film while having the exact actors in mind. It all happened within a period of a month from conceptualising, writing, prepping and shooting. Things were coming together very nicely which made me feel like this film was meant to be made at this point. I spoke to my producer and friend Dina Emam and asked her if she would come on board and she did. Dina took the big load of pulling the production together while I was doing my job as a director.

Still from ‘I Say Dust’ courtesy of Darine Hotait.

WK | I know from previous interviews, you’re also one of the few filmmakers delving into science fiction in Arabic, a genre that currently seems to be a bit brushed aside. How do you decide on what other narratives to highlight (for example: futuristic Beirut in 'ORB')?

DH | I am very interested in the technological advancement in all fields. I follow what's happening in the science world and robotics. We are now witnessing a marking point in history. Since the human's life is exponentially guided by technology, it is evident to me as a storyteller that this factor must become part of my narratives. I think science fiction is a very genuine genre that people have completely misunderstood or has been exhausted by Hollywood. It is highly needed to reach the Arab audience, in their language, with matters that they only think can happen in the West, which for me in itself is disastrous. Why can't we see films talking about science, technology, robotics, the future, produced in the Arab world? Can't we take part in this historical advancement, not even on a movie set?

WK | How do you avoid erasure and still stay loyal to your attempt to represent Arab characters as normative and comprehensive individuals? In the movie the subtle signs of ethnicity, the choice of make up, jewellery, etc., is never overwhelming, the main characters are first and foremost humans, who happen to be Arabs. How do you mitigate this balance to ensure your characters are never hyperboles?

DH | Less is more, especially when it comes to making films. As you said, the main characters are above all humans. My choice of actors was based on the natural signs of ethnicity that each one of them carried. So I [did not have to] worry about their physical appearance nor their accent. I wanted to stay true to the identity of those characters that I was presenting. With 'I Say Dust,' I wanted to break some barriers with the general stereotyped portrayal of Arabs and Arab-Americans in particular. As an Arab myself, and having lived in the United States for a long time, I think it wasn't hard for me to stay loyal to the real individuals I was attempting to portray. The characters in the film appear as they do in real life, and I wasn't trying to make them more or less Arab. They were themselves in many ways. So ensuring the believability of the characters was a matter of staying authentic and eliminating clichés. I knew the characters so well and I own the story so well that it was almost impossible to fall in the hyperbole gap.

WK | Are you worried about backlash from the Arab community?

DH | I wouldn't say I am worried. I am aware of the rejections that the film might face in some countries and certain film festivals in the region. However, I was completely amazed when I recently learned that the film was selected to be screened at the Afghanistan International Women's Film Festival. I loved the idea that this film spoke to them and they wanted it to be seen by the community. I know that there will be backlash from those who only want to read what's apparent and not scratch the surface of the film and understand the themes behind it. The film is for them anyways. I know at some point the idea will render.

WK | The film explores issues that are certainly relevant to most of us in society today (gay rights, transitory existence/idea of home), regardless of background. How do you find the ability to make it universal while still specific?

DH | I sincerely believe that if you want to make art universal you must be specific and particular. It is the detail that makes people connect with someone or something. 'I Say Dust' discusses the human's need to belong whether to a place or a person or a belief or even an idea and the various point of views that form our contradictions. Having two Arab women fall in love, argue home and identity, engage in a chess battle, and express themselves through the power of the spoken word, well the story can't get more specific than that! Yet, the film is about what makes home and how love can make us and break us. So at the same time, it can't be more universal.

Still from ‘I Say Dust’ courtesy of Darine Hotait.

WK | How do you plan on bringing regional conversations to an international stage?

DH | I rarely plan anything. If what I am doing speaks to the audience then it will make it to the international stage regardless of my efforts. If you come to think about it, our regional conversations don't need an international stage. That's where they fail to do what they're supposed to do most of the time. We need to have our conversations on our own stage first. Conversations with each other.

WK | What themes do you find yourself constantly reverting back to?

DH | I am very intrigued by human nature and sensibilities, detachment and uncertainty, perplexed conscience, guilt and virtue, resentment, brutal honesty and above all, the hidden powers of observation.

WK | How did your film production house Cinephilia come about, and what are you trying to accomplish with it? How does it differ from others?

DH | Cinephilia is an independent film production house dedicated to developing and producing content from and about the [Middle East and North Africa] MENA region. With Cinephilia, I am trying to present a resourceful space filled with opportunities where we do not set any boundaries for the filmmakers to create. At Cinephilia, and especially through its development labs, we give a great amount of attention on the quality of content that we develop and its resonance.

Our priority is to make films that speak the language of the countries where they originate. We want films to reach people from within and speak to them and reflect their realities and their fantasies on the big screen.

WK | Do you have any projects in the pipeline?

DH | 'ORB' [is currently] in pre-production which is meant to help in the financing of my science fiction feature film 'Symphony of a Flood.' [This film] tackles similar themes in a near future Beirut. I am also in the process of writing a new feature screenplay that takes place in Togo in collaboration with producer Jessy Chalfoun. And finally I am attached as a producer on the second feature film by Egyptian director Ayten Amin (Villa 69).

darinehotait.com

Wided

Rihana Khadraoui is an Algerian-American writer and founder of art

consultancy firm tazuri, which focuses on collaborating with emerging

creatives across the Middle East and North Africa. She’s passionate

about projects that enhance and promote MENA identities, both within the

region as well as the diaspora.