Hayv Kahraman: On Journeys and Translations

Author ········· Rania Jaber

Published ······ Online, Mar 2016

Section ······· Art & Design

Published ······ Online, Mar 2016

Section ······· Art & Design

A

good way to think about journeys is through the idea of translation.

Translation is the act of carrying something (whether it is tangible or

intangible) from one place to a different context. It is also the

necessary role enacted at certain junctures when an individual migrates

between two or more cultures and languages. The absence of language and

home that are brought about by displacement, conflict, war, and

migration are conditions that haunt the work of Hayv Kahraman.

It is the distance between the artist, her lost home, past

recollections, languages, and places that are questioned through her

artworks.

Hayv Kahraman’s work evokes several journeys. The first involved fleeing Iraq to Sweden during the Gulf war in 1991. Up until then, she had attended an International school in Baghdad and spoke both English and Arabic. Both of her parents were linguists who taught at a university in Baghdad. Although Kahraman and her family left with the command of two languages, they encountered a third language in Sweden and found themselves as outsiders. The only way to belong was to become like everyone else and to metamorphose oneself into speaking like others. She felt colonised, being in a context where everyone around her looked different and belonged to one culture. She wanted to be part of something that was not yet a part of her. One method was to learn Swedish and imitate others’ accents, so as to sound like them and diminish the tangible separation felt between people. But how could she change her appearance? Her dark hair and features gave away the noticeable fact that she was from somewhere else. These are the complexities and particularities of identities that are worthy of being rebuked when one is young.

Such memories inform the artist’s works and are composed of melancholic, humorous, and often heart-wrenching encounters and experiences. Her artwork helped her come to terms with herself and her past journeys. When Kahraman was studying graphic design in Florence at the age of 22, she was repetitively sketching a figure with dark hair and familiar features. The figure, influenced by the style of Renaissance painters, became a recurring and familiar character in Kahraman’s stories and renderings. Yes, she may be the artist herself, yet in the form of representation she is also a rendering all on her own accord. It was the artist’s way of coping with life incidents and creating a visual incarnation of her experiences, which represent an affinity with inner conflict and pain.

During an interview, Kahraman led me through her creative process where much research and translation is involved. Kahraman often begins with an idea that is then propelled forward by intense research. She enters a project through layers of investigation. In an obsessive way, she digs through the material persistently, like an archaeologist attempting to uncover layers and years of thinking. She connects each concept to its visual form, sketches it, and an idea takes shape. In a way she restages her memories onto the material she is working with. Most often she works with linen that she stretches and covers with glue made from rabbit skin so as to maintain a sheen surface. The framing of the work is largely dependent on each project. For example, the series Waraq (2010) was structured in the shape of a deck of playing cards representing fourteen migrants, while Let the Guest be the Master (2013) was documented on replicas of blue prints of old Iraqi houses.

Layer upon layer of experiences unfold on Kahraman’s canvas. She always knows exactly what she will paint before she has painted it. Each step is carefully calculated; there are few accidental mishaps on the canvas. Let The Guest be the Master (2013) was produced at a time when her father decided to sell the family house in Baghdad and all of a sudden she had no tangible place that she could call home. The loss of a home was akin to cutting her mother tongue, and losing her memories. She decided to archive her lost home by recreating it through this series. Each line became a trace of the walls in the house. She conducted extensive research about typical houses in Baghdad and recreated homes with courtyards, which still exist, while others have been demolished. The female presence in these houses formed a large part of each recreation. As a feminist strategy, it was the men who were absent from the architectural mappings of the houses.

![]()

Fragments of House (2013) from the series Let the Guest be the Master, Oil on wood, 147.3 x 281.9cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

In all the variegated movements to numerous places: Iraq, Sweden, Italy, and the United States where she currently resides, Kahraman carried across her personal archive of memories. Some were still fresh while others had been crumpled and needed to be unfolded. All these memories were recreated and re-imagined in different contexts. The migrants in the Waraq (2010) series reflect a trajectory of deep pain for individuals who have been uprooted from a home, and had to recreate themselves in another place. It leaves the viewer dumbstruck and in deep pain to think about the desperate need of the character to amputate her own mother tongue, both physically and metaphorically. To cut one’s mother tongue does not signify it has been lost, yet the self has been fragmented. In my interview with the artist, Kahraman talked about how this leads people to lose part of who they are. Yet, for the migrant who cuts her tongue to form a slash from her past, the sliced tongue may return in another format. To cut is to create an incision between the past and to work with the loss, which results in an injury that will eventually heal.

![]()

Migrant 3 (2009) from the series War-aq (2010), Oil on wooden panel, 177.8 x 114cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

Kahraman does not explicitly work with language. Yet, for the series How Iraqi are You? (2015) she was committed to not only revisiting her past memories, but also to re-learning her mother tongue of Arabic. The act of reliving moments and relearning what one had once learned is wrought by her autobiographical journey. In this series are experiences of almost forgetting a language she grew up hearing because it had to be replaced by another. Her own past, as well as Iraq’s history, were the propellers behind Kahraman’s research. The artist mends the severed tongue by re-learning Arabic. The works in How Iraqi Are You? (2015) were triggered by the artist’s own responsibility in transmitting the Arabic language to her daughter allowing Kahraman to perform as a translator and storyteller.

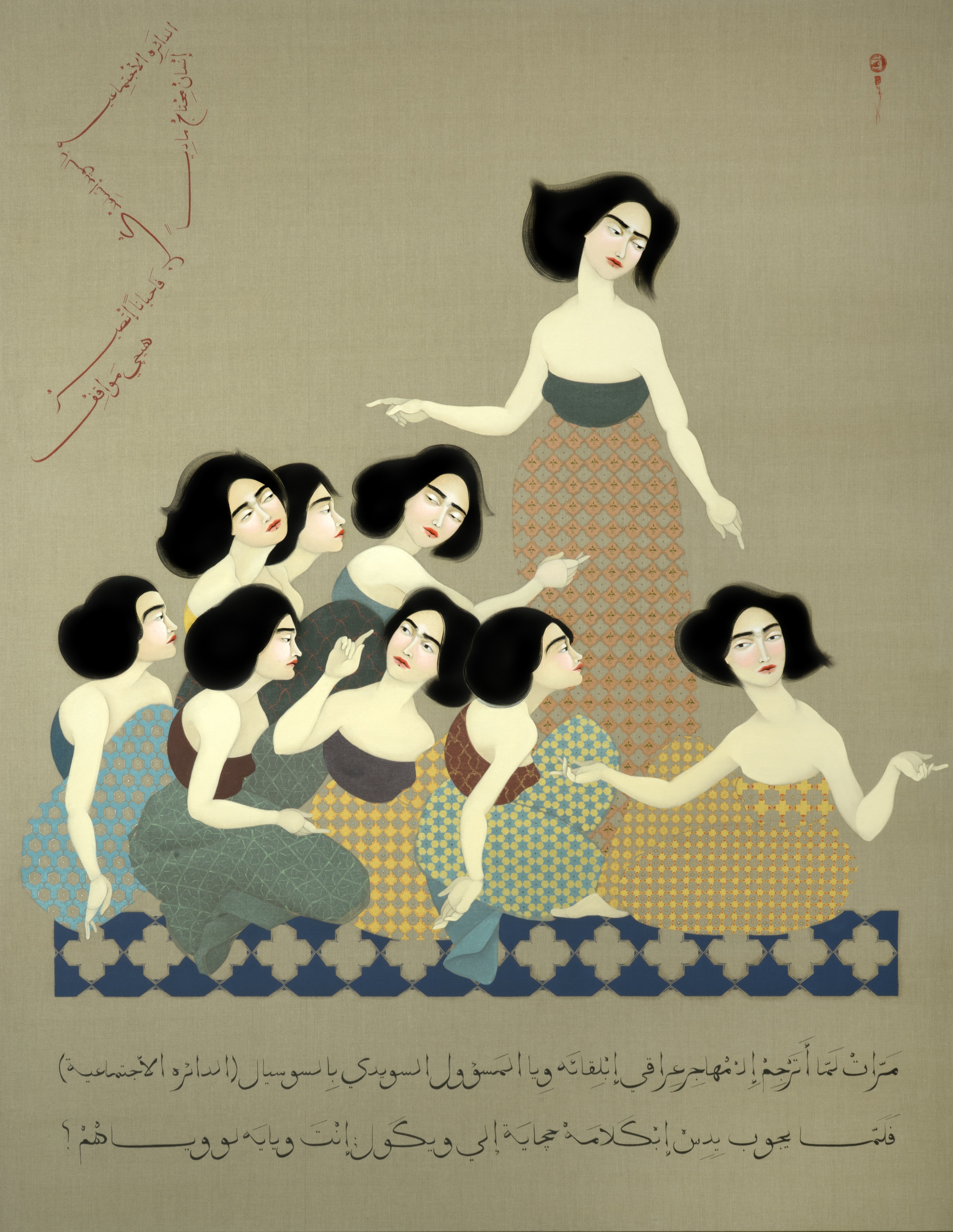

In the work The Translator from the same series, Kahraman restages an incident when her mother – who was able to speak both Arabic and Swedish –was the translator between aid workers in Sweden and Iraqi refugees. A heated debate ensued during which a refugee turned to Hayv’s mother and asked her which side she is on. Taking sides is an all too familiar political dialogue that has been propagated by the so-called war on terror and largely instigated by hegemonic powers. Although this painting is an enactment of an incident that Kahraman clearly remembers, it is also posing an integral question into the role of the translator who is often requested to choose sides. What about a third diasporic option in which the translator transcends sides? In dealing with uprootedness, Kahraman adheres to decontextualised enactments, moving beyond sides, political motions, and places. Rather, her characters simply exist through the stories they tell and are far removed from context, yet highly politicised on their own.

![]()

The Translator (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 249 x 193cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

In choosing to work with classical Arabic that has been recreated in the same style as the Maqamat al Hariri (The Assemblies of al-Hariri), she is reproducing a lost history. Every mention of these precious documents will inform spectators about historical resurrections and the necessary task of retrieval. They also provide a didactic understanding into artistic forms that have become obsolete. The Maqamat Al Hariri were a set of illuminated manuscripts from the 12th Century representing the Baghdad school of miniature painting. The artist was drawn to the expressive figures in these miniature paintings, which reflected daily life in Baghdad. The return to these narrative forms reveals the problematic of an unfinished history, interrupted by invasions, incursions, wars, colonisation, and migration.

![]()

Detail of The Translator (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 249 x 193cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

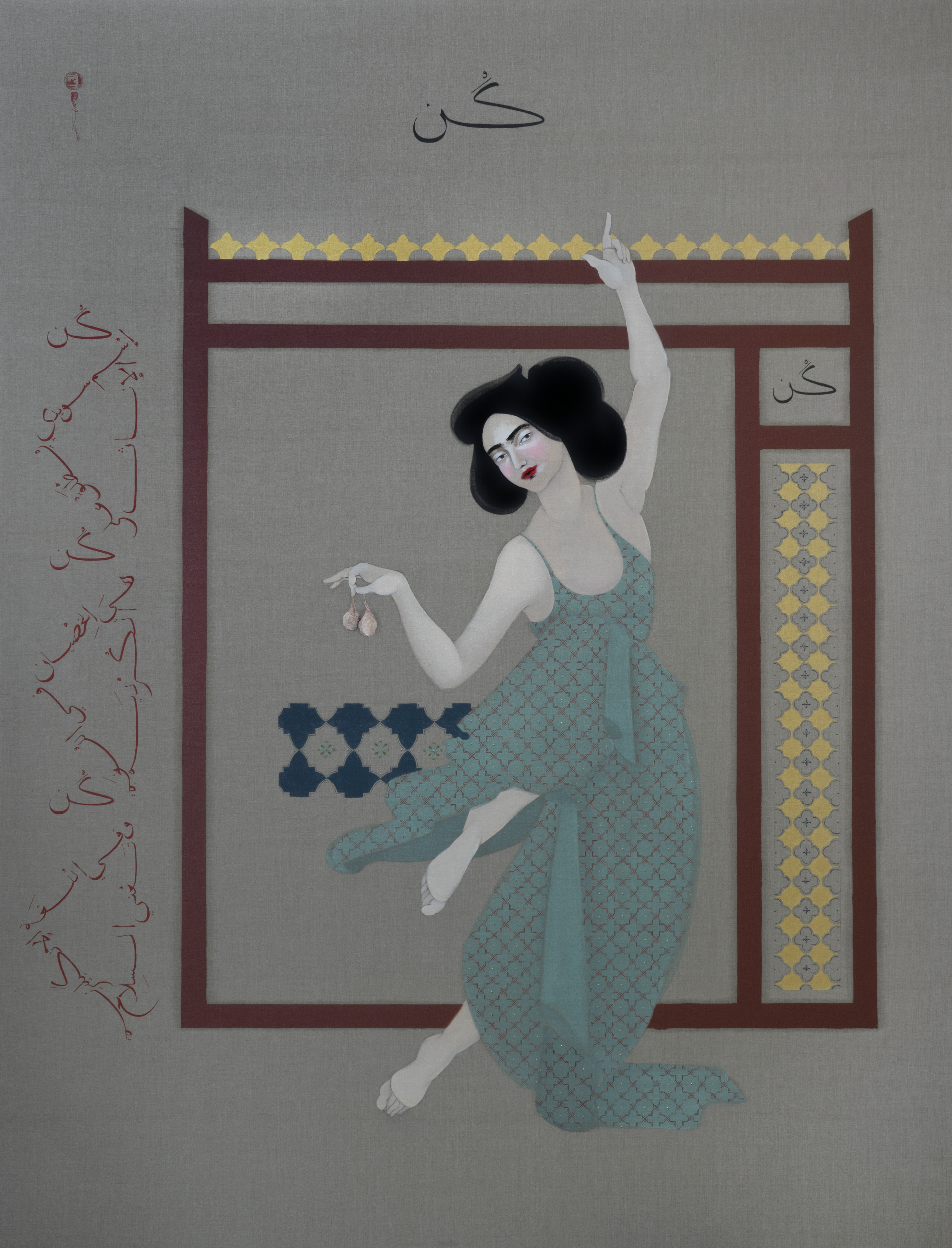

For this series, texts and words were crucial in speaking about Iraq’s history and past. In wishing to transmit this history to her daughter it was imperative that language was also the necessary tool for transmission. Kahraman shifts between cultural worlds, political spheres, and languages. Yet, a language becomes hers and a mother tongue expands and stretches across continents. At times, there are meanings to certain words that are retained even as they are carried across into different contexts. One such play involves the word “gun” which is self-evident in English, while in Swedish it references a girl’s name and finally in Kurdish, the word means testicles. Kahraman studied calligraphy and restaged similar narratives. She considered each letter, stroke, and space framing for each word. She claims that the progression with writing each word is evident in her paintings, as the series became a language archive where she relearned how to write again.

![]()

Her Name is Gun (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 244 x 185cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

How Iraqi Are You? was shown for the first time in New York at the Jack Shainman Gallery. It was an interesting reception where the artist decided not to provide translations for each painting. Viewers who did not know Arabic were unable to access the text, hence creating a division between insiders and outsiders in the same way that she was unable to access Swedish. It was her turn to be on the inside, rather than on the periphery.

Yet, amid entering the narrative and observing from the margins, she creates a space that is inclusive. For those who were able to decipher the text, and for the audience members who were part of the Iraqi diaspora, many related to the narratives and provided their own for her to document. They remembered some of the well-known sayings she had used, some of the fables, and shared their own stories and memories with her evoking a shared history through the series of artworks.

![]()

Detail of Her Name is Gun (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 244 x 185cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

Kahraman does not shy away from the potency of autobiography. Whether it is through narration or visual form, it is about her journeys and memories. The voice of the character is hers. The female figure is the artist’s conduit, yet they are both storytellers. Often, they are narrating the same story about migrants, mother tongues, cultural heritage, gender empowerment, alienation, and feeling out of place. Yet, through the artist’s journey, one realises that a feeling of belonging has to be created and the only way to do that is through the objects carried by agents in a diaspora; a condition that has been documented so extensively as an in-between space where one is constantly searching for the impossibility of place. Some have called it as a space occupying the best of both worlds. However, it remains to be determined. For now, it is a good strategy, at least one that accords a perpetual journey.

hayvkahraman.com

Hayv Kahraman’s work evokes several journeys. The first involved fleeing Iraq to Sweden during the Gulf war in 1991. Up until then, she had attended an International school in Baghdad and spoke both English and Arabic. Both of her parents were linguists who taught at a university in Baghdad. Although Kahraman and her family left with the command of two languages, they encountered a third language in Sweden and found themselves as outsiders. The only way to belong was to become like everyone else and to metamorphose oneself into speaking like others. She felt colonised, being in a context where everyone around her looked different and belonged to one culture. She wanted to be part of something that was not yet a part of her. One method was to learn Swedish and imitate others’ accents, so as to sound like them and diminish the tangible separation felt between people. But how could she change her appearance? Her dark hair and features gave away the noticeable fact that she was from somewhere else. These are the complexities and particularities of identities that are worthy of being rebuked when one is young.

Such memories inform the artist’s works and are composed of melancholic, humorous, and often heart-wrenching encounters and experiences. Her artwork helped her come to terms with herself and her past journeys. When Kahraman was studying graphic design in Florence at the age of 22, she was repetitively sketching a figure with dark hair and familiar features. The figure, influenced by the style of Renaissance painters, became a recurring and familiar character in Kahraman’s stories and renderings. Yes, she may be the artist herself, yet in the form of representation she is also a rendering all on her own accord. It was the artist’s way of coping with life incidents and creating a visual incarnation of her experiences, which represent an affinity with inner conflict and pain.

During an interview, Kahraman led me through her creative process where much research and translation is involved. Kahraman often begins with an idea that is then propelled forward by intense research. She enters a project through layers of investigation. In an obsessive way, she digs through the material persistently, like an archaeologist attempting to uncover layers and years of thinking. She connects each concept to its visual form, sketches it, and an idea takes shape. In a way she restages her memories onto the material she is working with. Most often she works with linen that she stretches and covers with glue made from rabbit skin so as to maintain a sheen surface. The framing of the work is largely dependent on each project. For example, the series Waraq (2010) was structured in the shape of a deck of playing cards representing fourteen migrants, while Let the Guest be the Master (2013) was documented on replicas of blue prints of old Iraqi houses.

Layer upon layer of experiences unfold on Kahraman’s canvas. She always knows exactly what she will paint before she has painted it. Each step is carefully calculated; there are few accidental mishaps on the canvas. Let The Guest be the Master (2013) was produced at a time when her father decided to sell the family house in Baghdad and all of a sudden she had no tangible place that she could call home. The loss of a home was akin to cutting her mother tongue, and losing her memories. She decided to archive her lost home by recreating it through this series. Each line became a trace of the walls in the house. She conducted extensive research about typical houses in Baghdad and recreated homes with courtyards, which still exist, while others have been demolished. The female presence in these houses formed a large part of each recreation. As a feminist strategy, it was the men who were absent from the architectural mappings of the houses.

Fragments of House (2013) from the series Let the Guest be the Master, Oil on wood, 147.3 x 281.9cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

In all the variegated movements to numerous places: Iraq, Sweden, Italy, and the United States where she currently resides, Kahraman carried across her personal archive of memories. Some were still fresh while others had been crumpled and needed to be unfolded. All these memories were recreated and re-imagined in different contexts. The migrants in the Waraq (2010) series reflect a trajectory of deep pain for individuals who have been uprooted from a home, and had to recreate themselves in another place. It leaves the viewer dumbstruck and in deep pain to think about the desperate need of the character to amputate her own mother tongue, both physically and metaphorically. To cut one’s mother tongue does not signify it has been lost, yet the self has been fragmented. In my interview with the artist, Kahraman talked about how this leads people to lose part of who they are. Yet, for the migrant who cuts her tongue to form a slash from her past, the sliced tongue may return in another format. To cut is to create an incision between the past and to work with the loss, which results in an injury that will eventually heal.

Migrant 3 (2009) from the series War-aq (2010), Oil on wooden panel, 177.8 x 114cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

Kahraman does not explicitly work with language. Yet, for the series How Iraqi are You? (2015) she was committed to not only revisiting her past memories, but also to re-learning her mother tongue of Arabic. The act of reliving moments and relearning what one had once learned is wrought by her autobiographical journey. In this series are experiences of almost forgetting a language she grew up hearing because it had to be replaced by another. Her own past, as well as Iraq’s history, were the propellers behind Kahraman’s research. The artist mends the severed tongue by re-learning Arabic. The works in How Iraqi Are You? (2015) were triggered by the artist’s own responsibility in transmitting the Arabic language to her daughter allowing Kahraman to perform as a translator and storyteller.

In the work The Translator from the same series, Kahraman restages an incident when her mother – who was able to speak both Arabic and Swedish –was the translator between aid workers in Sweden and Iraqi refugees. A heated debate ensued during which a refugee turned to Hayv’s mother and asked her which side she is on. Taking sides is an all too familiar political dialogue that has been propagated by the so-called war on terror and largely instigated by hegemonic powers. Although this painting is an enactment of an incident that Kahraman clearly remembers, it is also posing an integral question into the role of the translator who is often requested to choose sides. What about a third diasporic option in which the translator transcends sides? In dealing with uprootedness, Kahraman adheres to decontextualised enactments, moving beyond sides, political motions, and places. Rather, her characters simply exist through the stories they tell and are far removed from context, yet highly politicised on their own.

The Translator (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 249 x 193cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

In choosing to work with classical Arabic that has been recreated in the same style as the Maqamat al Hariri (The Assemblies of al-Hariri), she is reproducing a lost history. Every mention of these precious documents will inform spectators about historical resurrections and the necessary task of retrieval. They also provide a didactic understanding into artistic forms that have become obsolete. The Maqamat Al Hariri were a set of illuminated manuscripts from the 12th Century representing the Baghdad school of miniature painting. The artist was drawn to the expressive figures in these miniature paintings, which reflected daily life in Baghdad. The return to these narrative forms reveals the problematic of an unfinished history, interrupted by invasions, incursions, wars, colonisation, and migration.

Detail of The Translator (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 249 x 193cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

For this series, texts and words were crucial in speaking about Iraq’s history and past. In wishing to transmit this history to her daughter it was imperative that language was also the necessary tool for transmission. Kahraman shifts between cultural worlds, political spheres, and languages. Yet, a language becomes hers and a mother tongue expands and stretches across continents. At times, there are meanings to certain words that are retained even as they are carried across into different contexts. One such play involves the word “gun” which is self-evident in English, while in Swedish it references a girl’s name and finally in Kurdish, the word means testicles. Kahraman studied calligraphy and restaged similar narratives. She considered each letter, stroke, and space framing for each word. She claims that the progression with writing each word is evident in her paintings, as the series became a language archive where she relearned how to write again.

Her Name is Gun (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 244 x 185cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

How Iraqi Are You? was shown for the first time in New York at the Jack Shainman Gallery. It was an interesting reception where the artist decided not to provide translations for each painting. Viewers who did not know Arabic were unable to access the text, hence creating a division between insiders and outsiders in the same way that she was unable to access Swedish. It was her turn to be on the inside, rather than on the periphery.

Yet, amid entering the narrative and observing from the margins, she creates a space that is inclusive. For those who were able to decipher the text, and for the audience members who were part of the Iraqi diaspora, many related to the narratives and provided their own for her to document. They remembered some of the well-known sayings she had used, some of the fables, and shared their own stories and memories with her evoking a shared history through the series of artworks.

Detail of Her Name is Gun (2015) from the series How Iraqi Are You? (2015), Oil on linen, 244 x 185cm. Courtesy of the Artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

Kahraman does not shy away from the potency of autobiography. Whether it is through narration or visual form, it is about her journeys and memories. The voice of the character is hers. The female figure is the artist’s conduit, yet they are both storytellers. Often, they are narrating the same story about migrants, mother tongues, cultural heritage, gender empowerment, alienation, and feeling out of place. Yet, through the artist’s journey, one realises that a feeling of belonging has to be created and the only way to do that is through the objects carried by agents in a diaspora; a condition that has been documented so extensively as an in-between space where one is constantly searching for the impossibility of place. Some have called it as a space occupying the best of both worlds. However, it remains to be determined. For now, it is a good strategy, at least one that accords a perpetual journey.

hayvkahraman.com

Rania

Jaber is a UK-based researcher interested in art, language, gender, and

translation. She is currently working on a PhD thesis titled “Artists

as Translators: Lebanese Women Artists in Diasporic Settings."