Don’t Shoot me, I can tell you a Joke: An attempt at reviewing Sayed Kashua’s book Native

Author ········· Anna-Esther Younes

Published ······ Online, June 2016

Section ······· Culture

Published ······ Online, June 2016

Section ······· Culture

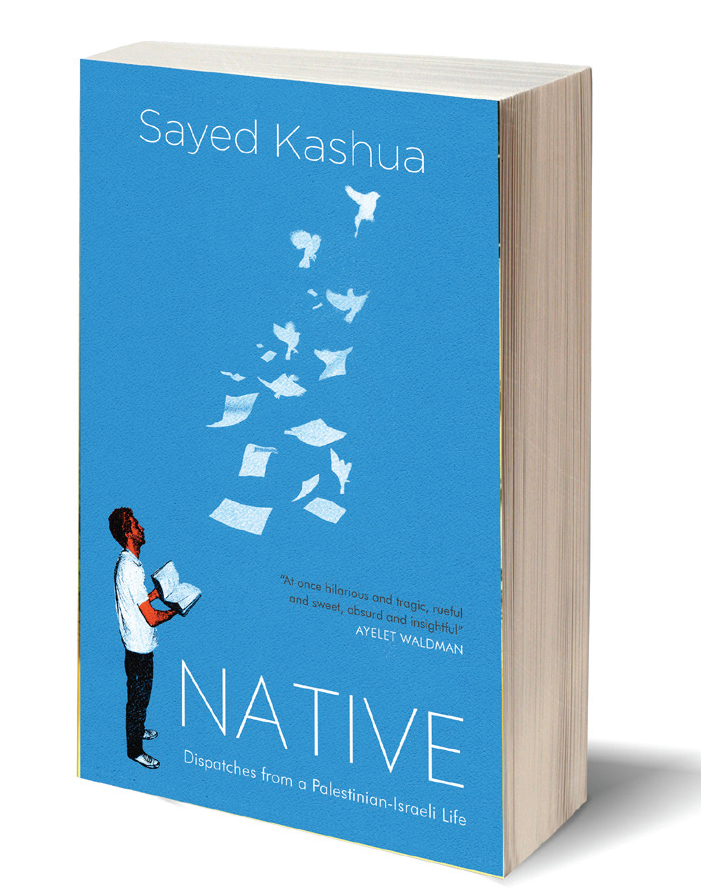

Image courtesy of Saqi Books

Jokes are always contextually situated and have the social function of sharing fantasies, realities and easing pain. They also bind people to each other, and, eclipsed in that function, can also serve to separate people from each other. Sayed Kashua is an example of all of that. Hailed as the hyphenated “Arab” humourist of Israeli society, he is a writer for Ha’aretz, whose weekly satirical columns from 2006-2014 are collected in the book Native – Dispatches from a Palestinian-Israeli Life. Kashua makes many Israelis laugh, but Palestinians don’t always necessarily always join in. What is important and controversial about his work is that he teases out a Palestinian identity for the reader that is inseparable from Israeliness. The everyday-colonialism of an Israeli citizenship is something that is indeed desperately in need of discussing, but most Palestinians are still unwilling to do so publically. For Israelis on the other hand, Kashua thinks that they relish the idea of a Palestinian engaging Jewish Israeli culture. Soberly, he explains in the book, “Everyone wanted to talk about identity, about nationality and foreignness, about detachment, self-determination. They wanted to hear about language, about humour and fears, and the future. And I drank a lot and thought about myself and this thing called a ‘Palestinian citizen of Israel’”.

Whatever side we talk about in this conflict, if we can talk about “sides” at all, all we can say is that humour is universal, but nothing is universally funny. Especially not in Israel and Kashua teases out its limits and possibilities. For instance, the disputed term “normalisation” is unapologetically taken to another interpretative level, when he writes that he turns on the well-known Israeli “Army Radio” in his car, because all other radio stations are playing songs that are too depressing for him. He talks about Palestinian voices that write better in Hebrew than in Arabic and that include the Yiddish nu in their daily vernacular. At the same time, he almost innocently confesses that he has “never been able to distinguish between good and bad, especially in writing”. For many Palestinians outside of Israel some of the issues are still difficult pills to swallow. For many Israeli Jews it appears satisfying to hear Kashua’s accounts in the wake of a power struggle where the recognition of some arbitrarily defined Jewish identity becomes the harbinger of national and political power. For the 48-Palestinians, it might be his very chutzpah that is appealing – of using his Israeli privilege to mirror the existential tit-for-tat of everyday colonialism by telling Israeli Jews “don’t shoot me, I can tell you a joke”.

What is humour in Kashua’s work and to whom is it directed? It seems he is unwilling to engage that question. Kashua rather presents himself as the anti-master of humour, one who never really understands what is going on and hence stumbles into situations that seem to be very ordinary but are strikingly “novel” for him every time. Might it be that the jokes he tells are more about his own (structural) repressions than about a funny situation? Is that why so many Israelis laugh about them? Do some people take the jokes not as an effect of repression, but as an affect of his naivety? Maybe one should write less about Kashua himself and more about how Israeli Jews and Palestinians receive his humour.

Native is built up into four parts where each of them is meant to represent a change in his writing. Usually one has to look for the political developments (including the wars) that accompany the years he is writing in. His silence on national politics seems intended and should thus be read as a political statement in his columns. Except in the last chapter, the one where he prepares to leave Israel, he talks history through personal experiences – the most political thing one could probably do in a settler-colonial state. Until then, however, Kashua deconstructs what a Palestinian, or generally speaking “the Other”, is supposed to be. Instead of writing like the “Other”, he writes like “Them”. There is a certain anxiety around the way he intends to write like those whose privilege grants them respect albeit disinterest, anonymity despite power: Thus, seemingly apolitically and “like everybody else” – aka Israeli Jews – Kashua writes about assembling a shoe-rack, getting drunk with women at Israeli clubs and bars in West Jerusalem, or obsessing over his partners un-/distracted attention, to name just a few examples. He plays with a mixture of surrealism and cynicism, adhering to a simple and successful strategy of feeding offense to those you aim to criticize: only talk about yourself, never about them. Yet, knowing full-well that his mimicry of Israeli Jewish ordinariness is bound to fail, he recurrently reminds the reader of the fantasy the privileged want to believe in: “I’m the kid who made it all the way from Tira [the Palestinian village he is from] to a black executive car. I am the one who will prove to everyone that it’s possible, really possible – you just have to believe”.

Image courtesy of Saqi Books

Kashua’s humour lives from a persona he calls a defeatist, addicted to cigarettes and alcohol. He also seems to think of himself as the embodiment of the system’s joke: a foolish anti-hero, an apathetic coward, one with whom one either feels sympathy or anger, rather than empathy or disgust. His first-person narrative-style lives from notorious lying and a defeatist desire to be like “them”. Kashua is well aware that Israeli Ashkenazi culture and education has suppressed and formed him. Thus, i.e., in his usual self-ridiculing way, he opens the book with a story, which ends by him telling passers-by’s in the Palestinian neighbourhood of Beit Safafa that “he is the only Ashkenazi in the neighbourhood”. He is well aware that the one, who wants to shine on stage, needs to be blinded by the light first.

The way he describes the daily micro-aggressions of colonialism and racism in Israel is simply to crack a joke about its ordinariness. Sometimes his jokes appear to be a survival strategy of someone whose security depends on deception; at other times it appears that his humour is a way of dealing with the anxious energy bound up in the Self, when being a subject at the whims of colonial education and power; yet on other occasions Kashua’s humour also appears as a neurotic character flaw, a “paranoid personality disorder” as his wife attests. Another option might be to think of it as a fusion of all these possibilities, embodying the inevitable characteristics of personal coping mechanisms amidst racism: whilst trying to avoid more pain one refuses the need to investigate its sources. A good example is his unsuccessful attempt to avoid being ushered into the lane for Arabs upon entry at the Tel Aviv airport. After some embarrassing moves to hide something that was never defined by him, he gives in to defeat, gets in line with the other “Arabs” and writes about finally “lowering his head” whilst “trying to be natural” in this.

Kashua chose to move his Palestinian family into an all-Jewish neighbourhood in West Jerusalem. He admits that his anxious integration work is built on the hope that one day his kids will have it better than him and his wife, by wanting them to be like those “white people who, when they grow old complain about the piano lessons they were forced to take.” Then, once his kids made it, he will be satisfied thinking, “They’ll complain about the violin; my daughter will complain about the piano. That’s what I call equal opportunity”. It is hard to escape his sarcasm at times. What is interesting about Kashua is that throughout the years, his identity becomes that of a Person of Colour who, for instance, sees the similarities of being an Arab in France to being an Arab in Israel. He realises that giving one’s geographical address plus an Arab family name when calling the electricity company (or the police, or an internet provider, or the ambulance, for example) actually dictates if help is on the way, or not.

The lesson he draws is that this position in society is not unique to Palestinians, but different. But the way he writes about his occupiers and friends is nevertheless with empathy and understanding even in the face of his own subjugation. In a way, one is reminded of Kafka’s Gregor Samsa (The Metamorphosis), who after turning into an animalistic creature still maintains compassion for his family’s tendency to inquire about “what he is” and “where to put him”, banning him to his room until, as they hope, it’s all over and Gregor will vanish by himself. Seen as an abhorrent creature by the family of man, Kashua and Samsa still have compassion, as long as the Other’s defining gaze is more powerful than one’s own knowledge about what is happening to oneself. However, at the end of the book, Kashua’s compassion and palsy seem to fade more and more and his new desire to move to the USA is expressed by him proclaiming that the only difference between the two countries is that at least in the US, everybody can have a gun.

His complete disillusionment in politics and political correctness reaches a tipping-point in the book, when the weather becomes more important than the national elections. A trope that should sound familiar in times of Trump, a failed Left, and rising fascism in Europe and India. About Israeli society Kashua attests that they “feel persecuted and threatened”, which for him fuels such structures. But apart from that analysis, there is more to Kashua’s depiction of a simple Palestinian trying to get along at the whims of a system that supersedes his own powers and understanding: political systems like the ones just mentioned depend on the characteristics he so favourably delineates in detail and with sarcastic nihilism in his stories. Hailed as exceptional, there is in fact only one thing all over Kashua’s columns, namely that he almost desperately tries to convey his ordinariness and helplessness to his readers. Interestingly, that goes mostly unnoticed in the majority of reviews or public endorsements one can read. Hence, in one story, he recounts being on stage in front of Israeli Jews whilst tragically, yet clearly, realising that “The image of a witty, funny, hurting man faded away and was replaced by a miserable wretch who constantly repeats himself as he attempts to wring laughs and sometimes also a few tears from an audience that mainly pities him.” Reading Kashua is thus also to understand that liberalism and democracy under specific conditions (i.e. colonialism) facilitate dehumanisation, even when one can laugh about the seeming normalcy of the effects of its divide-and-conquer matrix.

In the last chapter, Nakba Day is not another day for a cynical story about another self-delusional attempt to integrate (one’s ego) into Israeli society. Instead, it becomes the day to commemorate his grandfather – who was killed in 1948 – and his late grandmother’s wisdom about the future, past, and present of human life even without speaking Hebrew. During this commemoration, he describes his (new?) revelation, that “a house is never a certainty, and that refugee-hood is a sword hanging over me”. After having ridiculed the possibility of kinship all along, and as a person who is ready “to risk [his] life on the altar of free expression” as he describes, he then goes on to finally touch the last taboo: Sumoud. Sumoud, the Palestinian idea to remain on the land by any means possible, is now called into question by Kashua’s unapologetic yearning to leave Israel. He lost hope.

Kashua is now a teacher in the Jewish Culture and Society programme at the Urbana Champaign-Illinois University, 600 km from privatised Detroit and polluted Flint, and living in a militarised civil society where 310 million guns revolve in a country of 320 million people. After having believed for such a long time that humour and writing could change an oppressive nation, he is frustrated by needing to admit, that he now realises that “power only respects power”.

This collection of Kashua’s short essays is important, not only because the humour he delivers is defined by a satirical self-account of everyday-colonialism that had lost its addressee long before it was written. Kashua’s satire is also important because the reality of Palestinians in Israel that Kashua portrays can tell us a lot about a colonial reality in the midst of an ostensible democracy. And although Kashua’s humour couldn’t save him from the realities of this world nor from disillusionment, it will be interesting to see what he will joke about in his new home – the United States of America – a new colonial state with an ostensible democracy.

Buy Native at Saqi Books

Dr. Anna-Esther Younes finished her PhD in Geneva and is currently based in Berlin. Her work focuses on questions of race/racialisation in Germany and Europe, psychoanalysis and race, colonialism, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and anti-Muslim racism in Germany and Europe. Recently, she published the German country report in the “European Islamophobia Report” in March 2016 and organised the first interdisciplinary and international Palestinian Arts Festival in Berlin (2016).