Deconstructing Hairy: the Myth of the Arab Male

Author ········· Muriel N. Kahwagi

Photos ········· Tarek Moukaddem

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Art & Design

Photos ········· Tarek Moukaddem

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Art & Design

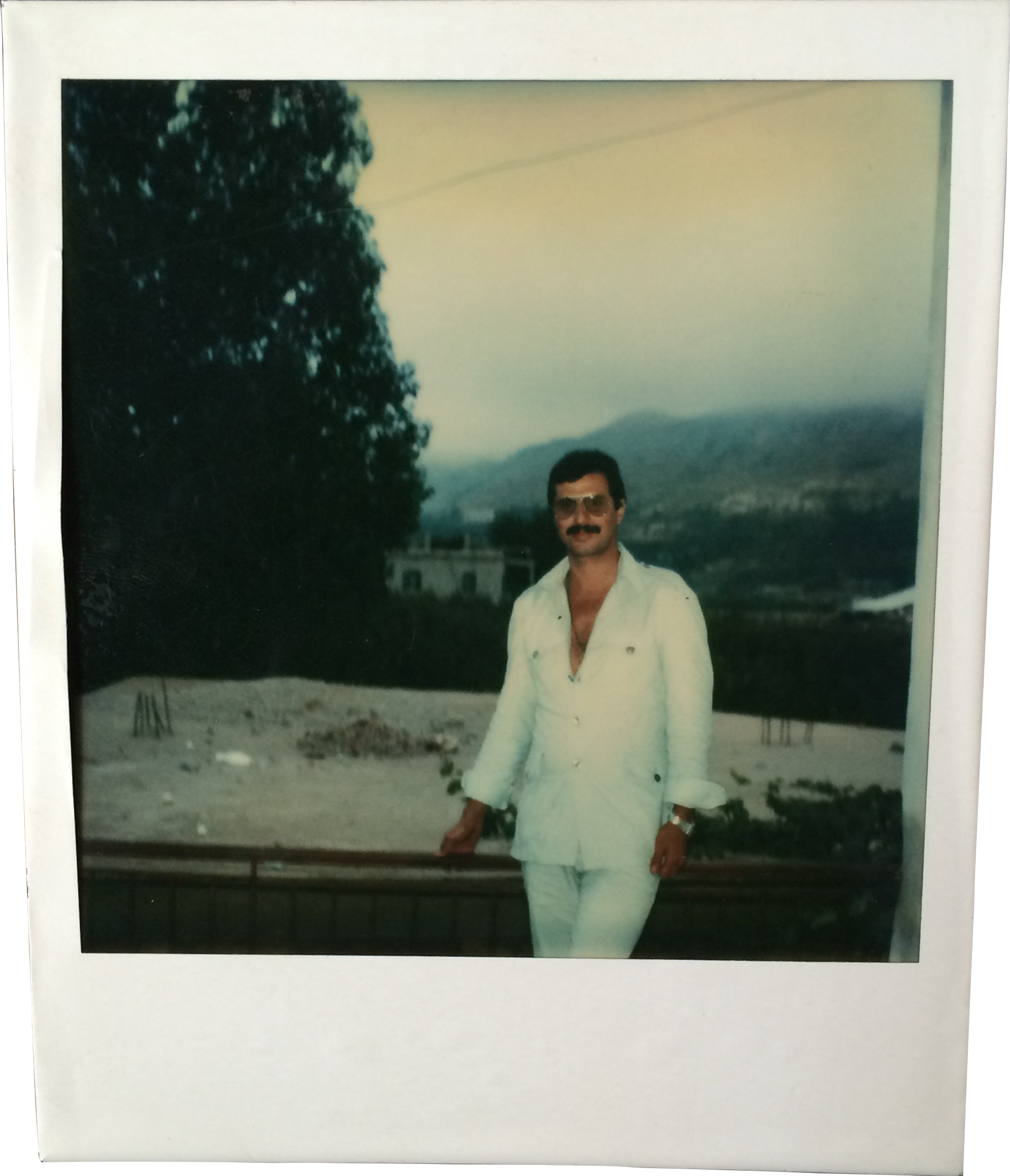

The author's father, Nabil Ibrahim Kahwagi, looking rad in 1979. Image courtesy of Muriel N. Kahwagi

The author's father, Nabil Ibrahim Kahwagi, looking rad in 1979. Image courtesy of Muriel N. KahwagiAmong my father’s treasure-trove of old comic books, memorabilia, and photographs is a Polaroid shot of him from 1972 against the dramatic backdrop of the Beqaa valley, sporting a moustache and a white corduroy bell-bottom suit. With one hand on his waist and the other in his pocket, he’s looking straight into the camera lens through dark shades, a few stray chest hairs poking through his deep neckline jacket. That a willowy man could get away with such ornateness in 1970s Lebanon seems unlikely, but as the archive of Hashem el Madani’s Studio Shehrazade confirms, that picture was all but an oddity forty years ago. When I described my father’s photograph to Charbel Kamel, a drama therapy student at Paris Descartes University, the general sentiment was one of wonder and ambivalence as we agreed that, were it to be taken today, that picture would raise more than a handful of eyebrows. “For many people in my family – and for Lebanese society generally – a man needs to be hefty to be manly,” says Kamel. “I’ve always been quite slender, and, growing up – even now, sometimes – it’s been frowned upon.”

“‘You need to eat so you can grow up and be a man,’” he burlesques his aunt’s taunting words. “My father, too, would try to get me to eat olives and asbeh nayyeh [raw meat] to encourage me to gain weight. I hate olives – they’re bitter! – and I was never a big fan of asbeh nayyeh. It’s as though your status as a man depended not only upon your weight and physique, but also on your diet. Certain foods, it turns out, are more masculine than others.”

‘Charbel’ from the Stvdio El Sham series

Standing at 5’10,” thick-bearded and bright-eyed, Kamel is an endearing mix of candidness and bashfulness. Comfortable as he seems in his own skin, he humbly admits that it wasn’t always so. “I was your typical ugly duckling as a teenager. Most teens are, I guess,” he jests. “I was constantly teased, not just because I was so skinny, but also because of my then-sprouting moustache. My face was quite pale, and my moustache so black and awkward in comparison, that my fifteen-year-old cousin at the time casually suggested threading it.”

Kamel recounts these comical episodes with great humour and generosity of spirit, and doesn’t shy away from asking himself – and me, in the process – the “big,” if hackneyed, questions that crop up therein: What defines a man’s manliness and masculinity? Is it the kind of food he eats? How much he weighs? The clothes he wears? The length of his beard? Or his V-shaped torso? In other words, is masculinity something that manifests itself, be it directly or indirectly, in a man’s body?

‘Philip’ from the Stvdio El Sham series

Studio el Sham, a photographic project conceived by Lebanese photographer Tarek Moukaddem and Palestinian designer OmarJoseph Nasser-Khoury, brings these questions into the spotlight in an attempt to explore the origins and social repercussions of assumed normative paradigms of masculinity in the Arab world. Currently a work in progress, the project seeks to challenge “the super-butch image of Arab maleness, especially the one framed by the ongoing colonialism, war, dispossession, and revolution.”

Kamel walked into Studio el Sham on a whim. “I’d been a big fan of Tarek’s work for quite some time, and when he posted a call for models for this project a year and a half ago, I wanted to get involved right away.” “I didn’t really know what it was about back then,” he admits. “I can’t tell you that I was drawn to the project’s premise, and that’s why I decided to do it. I know that this is probably the answer you’d like to hear, but that’s not what happened, and that’s not why I did it.”

‘Abu Zuhair’ from The Official Portrait series

“In retrospect, though, I can put some of the pieces of the puzzle together, if you will, and in some ways, I am more aware of my subconscious motivations for wanting to get involved in something like this.” In his Studio el Sham photograph, Kamel looks both composed and unselfconscious. With a beanie over his head and a pair of round, metal-rimmed glasses over his eyes, he stands tall and graceful, carrying a sword in his two hands. Despite his being shirtless, there is nothing about his demeanour – nor about any of the other models’ – that inspires provocativeness.

‘Abu Saleh’ from The Official Portrait series

“My work with Tarek is usually unabashedly erotic, but always resists the stereotype of the pornographic,” explains Nasser-Khoury. “The challenge is to strip masculinity of the macho without emasculation. The lush sensuality of the photography is in itself a critique of the decadence these characters represent.”

“Masculinity is something that is very personal to an individual,” he goes on to say. “I don’t think you can explore any of these concepts or ideas if you haven’t gone through them or experienced them yourself. But it’s also such an ambiguous word now, and we’re trying to disentangle it in terms of what it means and what it inspires when people hear [the word “masculinity”], so ultimately, it is not a fixed idea with a fixed meaning; it’s a positionality.”

‘Joe’ from the Stvdio El Sham series'

For Moukaddem, however, Studio el Sham is “more of a game.” “I’m fascinated by these old Levantine studio images and their inherent performativity. You can take pictures with your phone very easily these days; it takes half a second,” he says. It is precisely this technologically-induced effortlessness that drove the pair to recreate a setting whereby people needed to make the extra effort, and engage in this kind of role-play. “So we put different kinds of clothes everywhere, and let them wear whatever they wanted,” he explains. “It was interesting for us to see how they wanted to represent themselves in this sort of setting.”

“But people also tend to forget that this idea of what is masculine and what is not, or what a man should or shouldn’t look like, was essentially invented abroad,” Moukaddem adds. “It only started being part of [Arab] culture twenty or thirty years ago due to globalisation. In smaller, less cosmopolitan Lebanese towns and villages, a man’s masculinity is more contingent upon things like pride and power. It’s not about what he looks like, or the degree of intimacy he shares with another man.”

omarivs.tumblr.com

instagram.com/tarekmoukaddem

Muriel N. Kahwagi is a writer based in Beirut. Her work has appeared in The Outpost, Rusted Radishes, and Moussem Journa(a)l. Together with James Brillantes, she founded Jizz&Jazz, a fictional

music and podcast producing duo that parodies normative paradigms of

conflict resolution in the Middle East. Currently, she is the head of

communications at the Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock Museum.