Art of Destruction – Culture & Heritage: an interview with Aseel Alyacoub

Photos ········· Jean-Paul Gomez

Published ······ Online, Nov 2015

Section ······· Art & Design

In a brilliant essay written by Timo Kaabi-Linke, titled “Geo-Coding Contemporary Art?”, Kaabi-Linke mentions how cultural terms in the arts are “used with unwritten question marks.” There has been a propensity, in art history, to classify and incorporate art into specific eras, styles, and movements. This tendency of selection and separation has always de-complicated the diversity and variety of artists and their works. However, in this day and age, and when countless intellectuals proclaim the epoch of ‘post-histoire,’ a fluid presentness with no time-lags nor period-breaks for temporal observations and categorisations, I find myself uncomfortable with geographic-based group exhibitions that continue to ripple across contemporary art institutions based on supra-regional, ever-so-diverse and controversial regions as the ‘Arab’ world. The failure of approaching the arts appropriately within this region allowed many important artistic voices to remain unheard.

I chose to interview one of these important voices. An emerging artist from Kuwait, Aseel AlYacoub’s thesis show reflects her theoretical practice in which she digs up Kuwait’s own archaeology of knowledge. AlYacoub interrogates official history by challenging Kuwait’s taken-for-granted cultural and structural episteme. From AlYacoub’s contestatory video work questioning the reasoning behind the prohibition of filming in public spaces, to the microscopic stamp collection created through the destruction of a national artefact, AlYacoub’s socially engaged practice proves to be a crucial deconstructing and demystifying tool.

TB | How did your piece Culture Fair come about?

AA | I began collecting postage stamps that reflected the peak of Kuwait’s modernity era. Propaganda on postage stamps is of a more subdued and discreet nature than that exhibited by other media and it has been given surprisingly little attention. Yet the fact that the postage stamp was, and still is, widely circulated and that it does not have an obvious message enhances its peculiar effectiveness. So the stamp itself is ideal propaganda. It goes from hand to hand and town to town; it reaches the farthest corners and provinces of a country and even the farthest countries of the world. Therefore, it is a symbol of the nation from which the stamp is mailed, a vivid expression of that country’s culture and civilization and of its ideas and ideals.

Culture Fair

I dissected and reassembled Kuwaiti stamps dating from 1960 to 1991. By cutting, rearranging and pasting them over each other, I am in some way destroying the national artefact and recreating the image with my own narrative. They are then displayed on jutting stud planks (2x4 inch) that have been stained in a rich dark brown and a magnifying dome is placed on top of each stamp. The image is magnified, expanding the collages to turn them into meaningful objects. They transform into museum or cultural artefacts usually found in culture or world fairs. It’s interesting to view people approaching them, as from a distance the installation is quite minimal and the shadows are an important factor. However, upon closer inspection the viewer tends to be pleasantly surprised and is somehow more fascinated with the labour and precision rather than the narrative itself.

TB | Can you give me an example of 'national artefacts'?

AA | Another example in this case could be Kuwait’s older paper money.

TB | Did Kuwait ever have a stamp as a national artefact?

AA | They can be seen as national artefacts today as the older stamps are no longer in use. For example, I found older stamps that used Rupees as a currency rather than Kuwaiti Dinars.

TB | Your collages are based on stamps that we had in the mid-twentieth century?

AA | Yes, they are not scanned copies but the originals.

TB | In a sense, creating your art through the destruction of another?

AA | That’s an interesting question. Can we label stamps as a form of art? Probably not, especially today. I would say I am creating art out of existing patriotic and national images.

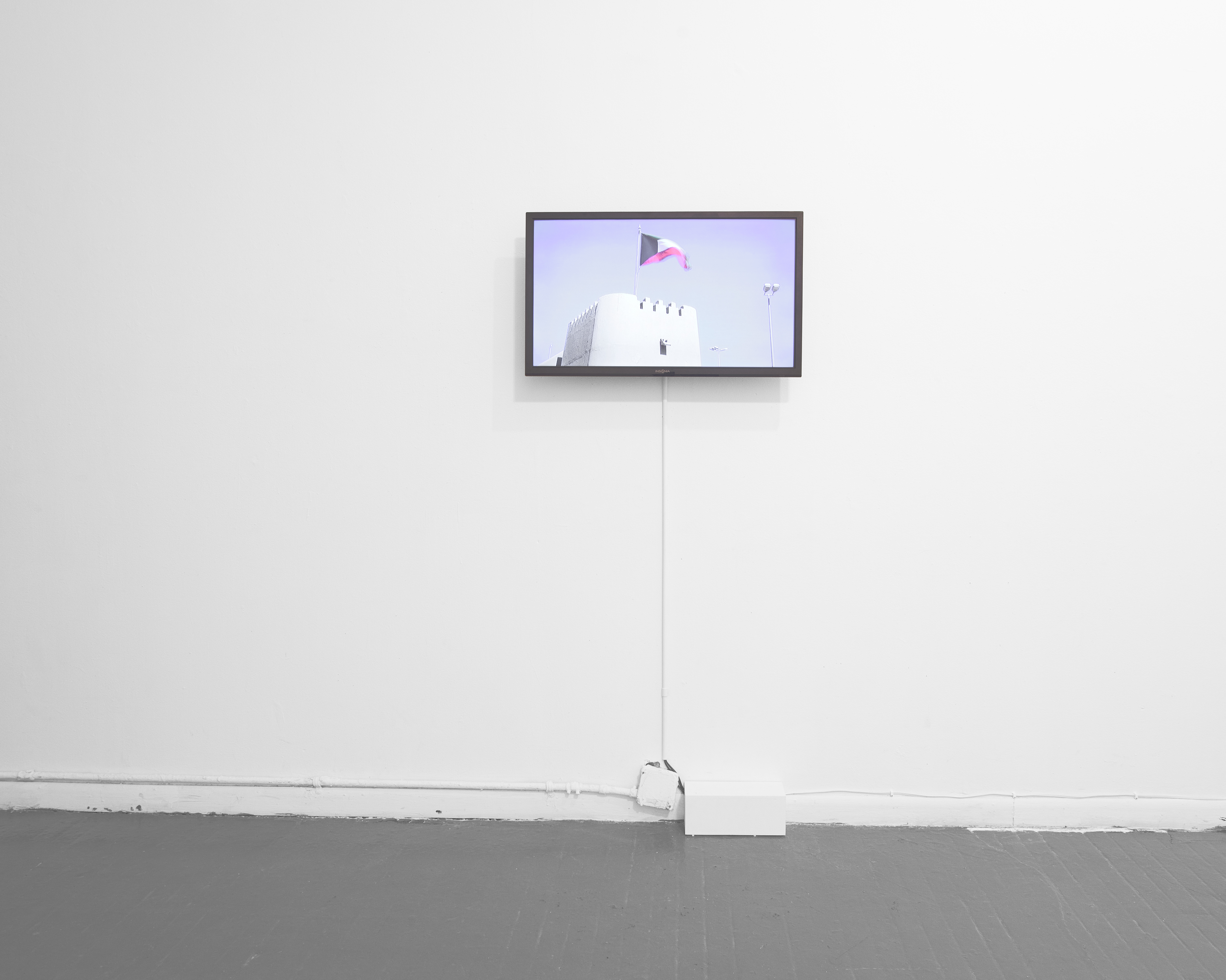

TB | Can you talk to me about your piece Heritage Wall no. 6?

AA | Heritage Wall no.6 is a simulacrum of Kuwait’s fort wall. That wall has been demolished and only the five gates remain.

Heritage Wall no. 6

Heritage Wall no. 6

TB | This one being…

AA | This one being the sixth and [it] exists in the gallery space right now. When Kuwait ushered its transition towards modernity, a series of master plans transformed Kuwait’s physical and social environment. The plan called for the demolition of old Kuwait to pave the way for a new state capital. Today only five gates remain and have recently been revived as ‘monuments’ of a recent past. They are considered to be heritage sites albeit being surrounded by highways and infrastructure. They are placed on inaccessible islands and can only be seen through a moving vehicle, a stoplight, or across the street if you are walking. They lose their significance as they are quite removed from the public.

TB | What does this wall signify?

AA | This piece stands freely, at an angle, in the middle of a white box gallery space. The corner is broken off and the interior of the wall and frame are exposed. Parts of the wood are stained, just like the piece Culture Fair, and also jut out from the side of the structure. The 2x4 inch stud is used again. A two legged chair balances on the long side of the wall, balancing a ‘reserved’ plaque on its lap.

TB | Can you elaborate on this?

AA | The stained wood reflects on the cheap methods used to recreate or renovate heritage sites. It seems as though a lot of the means of preservation in Kuwait are not quite well thought through. In this piece, I’m questioning the renovations of the original heritage walls as you can also see in my other work Checkpoints. The broken edge is a motif for age and time, a fake memory of the original wall that was beginning to fall apart.

TB | What kind of wood is this?

AA | It’s a basic 2x4 stud plank used to build dry walls. You can see the structure from the right side of the wall and the deception of its sturdiness. I could have made the wall out of bricks or poured concrete, however I wanted to emphasise the theatrical imitation of places and objects. The exterior wood is sanded and stained in a rich dark brown and the interior is left in its raw form.

TB | Luxurious.

AA | Yes, the stained wood gives the feel of care and attention. However, it only appears that way from the outside.

TB | So this broken chair, with only two front legs grounded on the floor, while the back is leaning on this blank wall, meaning the sort of blind faith...

AA | It’s interesting that you see the blank wall [symbolising] blind faith. The chair’s weathered appearance, physical dysfunction, and dependence on the structure are a metaphor for social dependency. It is the idealism behind the national collective history. The reserved sign just pokes at its importance. This chair was inspired from my two works Embargo and Checkpoints. Although you don’t see them in the films, both security guards were using a white patio chair to guard their spaces. It’s an object that has an invisible recurring theme in my work.

TB | What’s interesting is the cultural connotation of this ‘found object.’ When I look at this chair, I think of endless birthday and school parties. But much more, I think of it as a strong nostalgic feeder. However, this chair looks so foreign here in this gallery. It’s simply a broken chair. What does it remind you of?

AA | سوق المباركية (souk al mubarakiya)

TB | But to someone else…

AA | Possibly birthday parties like you. [When I lived] in Brooklyn, close to a Puerto Rican neighbourhood, I saw them being used on the streets quite a lot. They’re also used in outdoor hookah bars in many countries.

TB | And so محجوز (reserved) is on the one side, and then on the other side it's in English. Can you tell me the most memorable, radical or random questions that people have asked you, if you have any?

AA | The only reason I presented Reserve in Arabic and English is because I’m showing this piece in New York. It’s challenging to present very specific works outside of the context in which these works originated from. I’m trying to expand access to the pieces, as many of the viewers attending will not know much about Kuwait. A visitor asked me where we were in this exhibition and I thought it was a philosophical question at first. But then I came to the realisation that he meant geographically because the images shown were foreign to him. Although the videos have Kuwaiti flags fluttering in the wind and the stamps are labelled with ‘The State of Kuwait,” it can be overwhelming to understand my work without a lecture on Kuwait’s history beforehand.

TB | Of course not. We're a tiny country known for little other than oil and wealth.

AA | I gave a talk about my work once and a member of the audience informed me that his perception of Kuwait was three things: monarchy, oil, and patriarchy. He was wondering why I wasn’t tackling gender issues.

TB | Before we get into gender politics, I want to go back to those three issues. We are a monarchy, we definitely have oil, and it’s definitely a patriarchal society. But the way we [Kuwaitis] see it is different than others, because we don't consider ourselves victims. At least, I don't. I think there's a wider issue to tackle, but I feel as though traces of it are evident or are embedded within cultures and religions. Most mainstream media is concentrated on our region. So what I like to argue against is that I don't see myself as a victim. I find that most people that sort of exploit this whole victimhood to the wider public, garner attention and empathy. It’s just unethical and unfounded.

AA | Some do exaggerate [victimisation] but to each their own.

TB | It's hyperbolic, definitely. And I like the fact that you don't infuse that in your work or showcase that. I appreciate your approach and framework of questioning: 'Let's talk about wider issues, let's talk about nation, let's talk about identity. Let's not talk about the fact that I'm a woman and I'm subjugated. And let's not talk about the generalities, about Islam, the monarchy, or this extreme sort of oppression.' But do you feel like your work, or you yourself in your practice tackle gender? Is that a theme of your work?

AA | It’s inevitable because I am a woman at the end of the day. I forget that sometimes and I am genuinely surprised when my work is addressed from the gender perspective rather than [its] original intention. In Embargo I can see how that is stronger as a gender power struggle than about the private vs. public or the local vs. the immigrant.

TB | I want to talk about your video work Embargo (2014). Can you tell me about this work?

AA | I wanted to document the transformation of Kuwait’s maritime shoreline. After visiting the Maritime Museum in Kuwait, I was fascinated by the way they displayed every object used when diving or sailing. There were old letters, record books, and photographs. The museum itself felt like you were walking on board an old dhow.

TB | Kuwait has a Maritime Museum?

AA | Yes it’s right next to the Museum of Modern Art, which was an old Kuwaiti school and is one of the few places in Kuwait that has been decently restored. I found out where the ports were and Marina Mall was one of the shores used for fishing and pearl diving. There are a couple of ports today that still have the old Kuwaiti dhows and you can hop on board and meet the fishermen. It’s a popular tourist spot. The rest have been transformed into public walk spaces and are usually in front of malls or clubs. They now host yachts and modern fishing boats. There are three other sites in the video so it’s not all in one port. However, the confrontation I received at Marina Mall altered the work completely.

TB | Speaking of the confrontation, you had all these questions: ‘who is enforcing this? Why?' to which the security guard didn’t have answers, but nevertheless, he parroted strict social orders.

AA | I think it’s always important for people to know the intent. I wasn’t going there to be confronted. I began censoring the video because of this confrontation. First, I censor[ed] the boats, then the buildings, and finally, everything apart from the sky and sea. To censor in Arabic is translated into raqabbah (to watch or oversee) rather than to access, edit, or suppress unacceptable material. Using censorship’s translatability, the film consists of three segments: the act of watching, being watched, and the ‘overseeing’ of the self. This progression is elicited by my interaction with the Egyptian security guard, a migrant worker who has his own restrictions to contend with.

Embargo

TB | The way in which you gradually blanket the view of the marina in Embargo highlights the subtle social censorship, particularly in public space.

AA | Social censorship is content for my work. I want to highlight the frustrating elements that we have to contend with today, especially in Kuwait. Both public and the private spaces in Kuwait have limitations and there will be social consequences if you express yourself or take action [that is] out of line.

TB | Likewise, when it comes to unwritten laws and the general state of affairs. It's true because I feel like for us – weirdly enough – a public space is more oppressive than a private one. How that conversation between you and the security guard, who was quick to stop you from filming, but once you asked him and questioned him, he just didn’t have the answers to it. It’s absurd– why can't you film? This is a public space. This ties back to an important theme we were discussing earlier: public vs. private spaces – this idea of self-control in public, controlling your actions and what you say, the subtle irony of the repressiveness in public spaces… Whereas here [Kuwait] there’s a totally different understanding of a public space. Going beyond social etiquette, public spaces are – contrary to popular belief – not enforced by the government or enforced by the authorities, it's actually enforced by people and our consequent culture and norms.

AA| The structures I criticise are not necessarily the obvious ones i.e. a government force. Rather, I am poking at the social authority that is quite assertive in itself. I am more interested in the public’s idea on vandalising heritage sites or tearing up collectible national stamps.

Towards the end of our interview, a fellow student walks by and asks Aseel about her sculptural piece, Sooner or Later. The piece is comprised of a 1950s Magnavox radio, a green shelf, an authentic orchard ladder, a leaking inflatable pool, two blue buckets, water, an electrical cord, power supply, and white noise.

Sooner or Later (left) and Culture Fair (right)

AA | This is the most metaphorical piece I've ever done. Usually it's a little louder than this, and the noise fluctuates back and forth. It's a very, very subtle oppressive feeling, where you walk in and you're really annoyed but you get used to it. [It describes] how I feel when I'm in Kuwait, [and] how a lot of people [feel] when they're in Kuwait – [this idea of being] seduced by the affluence or this idea of the collective pool, 'We all belong here.' But there's a structural hierarchy that is very precarious. Although inviting, it seems easier to manage or tackle, it's actually not something that you would really want to do. So the obstacle is sort of testing your fight or flight mechanism. Once you leave the room, you feel a sense of relief, and you notice the noise and that soft oppression. That's how I feel whenever I leave Kuwait.

Student | Is it because you feel oppressed from the government?

AA | More than anything, I think it's the social structure. The idea of what you can and cannot do. In this piece the social hierarchy is proposed both in its formal figurative appearance and sensual experience.

Student | So how does one define Kuwait? The body politic?

AA | Kuwait is a nation like any other. It consists of a group of people that are associated with that particular territory. It is a patriotic nation and is adequately aware of its unity. It is a constitutional emirate with a semi-democratic system. The political system is a hybrid divided between an appointed government and an elected parliament. It is a handicapped democracy in my opinion.

TB | Reverting this back to your artistic practice, it seems to me that you started with a framework for the show, then criteria and a mode of evaluating, and without the framework, your thesis show would be a hodgepodge of free forming ideas disengaged from any systematic, coherent analysis. Do you find that your ideas are paramount, and material secondary?

AA | It really depends, but you’re right about this show. Although I made a lot more work over the two year MFA programme, I had to select works that could converse with each other. I wanted a looping obstacle course that brings you back to the same question. My ideas stem from research but the concept I present is as important as the finished product. My thesis was a study of nostalgia and I’m trying to use it as an instrument for critical thought rather than the longing for the past. This allowed me to investigate the invention and reinvention of heritage and tradition. I was, and still am, fascinated with the past and how it emerges into the present. But the most interesting part of this show will be the irony; I will have to demolish Heritage Wall no.6.