Acquiring Modernity, Acquiring Meaning?

Author ········· Shoag Al-Adsani

Published ······ Online, May 2015

Section ······· Art & Design

Published ······ Online, May 2015

Section ······· Art & Design

Between July and November 2014, Alia Farid and a team of researchers

hailing from disciplines including art, architecture, literature, film

and music, exhibited the Pavilion of Kuwait at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia.

Their multifaceted project, modest in its appearance at the Arsenale,

was boldly critical and confrontational in what it generated around the

upshot of the pavilion.

Together, the team produced a volume of essays and photographs regarding the nation’s history of modernisation; a short film entitled Muneera based on the story by Khaled Mohammed Al-Faraj; a collaboration with the Nordic Pavilion to install a drinking fountain (sabil) in Venice, emblematic of Kuwait’s relationship with Danish architecture; lectures and talks regarding the work and research; as well as the actual pavilion itself. The combined efforts of the team resulted in a comprehensive and unprecedented amount of research and critique of architecture, modernity, affluence, and cultural space in Kuwait.

I had the opportunity to attend the Acquiring Modernity Symposium at the National Library of Kuwait last December, in which Alia and fellow team members Dana Aljouder, Aisha Al Sager, Sara Saragoça, and Hassan Hayat spoke on demolition, preservation, public space, and identity. I spoke with Alia, a Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican visual artist who works at the intersections of art and architecture, about the experience working at the Biennale, her thoughts on architecture and local action in Kuwait, and bringing our famous blue and white water fountains to Venice.

AF | The overarching theme and title for the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia was Absorbing Modernity. It was a call asking all participating countries to consider how modernity affected local culture, and for the first time in the history of the architecture biennale the exhibition was being envisaged as a retrospective. Up until 2014 when Rem Koolhaas became director, the biennale had been about representing and highlighting current and future work of prominent or promising architects, but never about looking back. It had never taken this kind of historiographic format/approach. I think everyone was really excited about this. For us in Kuwait, it meant an opportunity to carefully think about what happened to a reverence once held for architecture, and why the city today is the way it is. It’s something a lot of people in the field ask and think about, like ‘shi’salfah’ (what’s the deal)? [laughs]. Where did we go wrong? And so this was a really good occasion to go back and really think about architecture – and the future of architecture – in Kuwait.

Coming from the Heritage and Restoration Department of the National Council for Culture, Arts & Letters (NCCAL), Kuwait’s government cultural organisation, it felt important to align the interests of the biennale with the work being done in the department. Let me explain: the department I was working for is in charge of preserving, restoring, and maintaining buildings of cultural and historical significance in Kuwait. They’re mostly concerned with pre-oil structures, i.e. mud-buildings. There aren’t a lot of these left in Kuwait, but the ones that are still standing are the ones the department is primarily “working” to preserve. The NCCAL has a dated and warped idea about conservation – it’s a common opinion. In a way, our project was not just about rethinking how architecture should be protected in Kuwait, but also about the selection of works preserved and ideologically what they imply. The project became about the future of architectural heritage and encouraging the NCCAL to include modernist architecture and vernacular structures as national monuments, such as the Al Khudhur Shrine on Failaka Island, which has been demolished twice because of sectarian disputes. Why should places like Bayt Dickson be preserved, and not the Al Khudhur Shrine? And why is the Kuwait National Museum (KNM) (Michel Écochard’s masterpiece) adulterated beyond recognition, same with Arne Jacobsen’s Central Bank design?

![]()

Tareq Sayed Rajab, the first appointed Director of the Department of Antiquities and Museums of Kuwait (1957) with a group of foreign journalists and archaeologists at the site of the Al Khudhur Shrine on Failaka Island. Courtesy of Tareq and Jehan Sayed Rajab.

SA | I found the subsections for the KNM to be really cool – the ‘Man of Kuwait’, ‘The Future of Kuwait’… could you elaborate on that?

AF | We decided to focus our participation on the KNM, and through its envisaged programme, expand on different subjects related to architecture and urbanism in the country. ‘Land of Kuwait’, ‘Man of Kuwait’, ‘Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow’– these are some of the themes the architect suggested to help the client’s imagination when thinking about possible exhibitions for the museum. Let [me] backtrack for a minute: the KNM compound is made up of four buildings. When the architect arrived in the 1960s to meet his clients (the Ministry of Education at the time) and ask what they planned on exhibiting, he quickly understood that no one knew. The architect then put forward a programme, supplying a headline-theme for each of the four buildings and the planetarium. He described the museum not as a space for the passive viewing of objects, but rather as a cultural space alive with objects and activity. In correlation with each of these headlines, we then organised our research.

![]()

Axonometric drawing of the Kuwait National Museum by architect Michel Écochard. Courtesy of the Aga Khan Foundation.

[Starting] in October 2013, we met every Saturday until our departure for Venice. We were a group of 22, each bringing information that we found from all over the place: family archives, the basement of the KNM, the Al Qabas Newspaper Archive, archives in London, Paris, Copenhagen, Cambridge… The headlines became a helpful way of structuring things. And because the KNM is managed by the NCCAL, the hope was that by focusing our participation on the museum, we’d be able to reactivate the space and get it into healthy, operating condition. Meanwhile, we worked out of the Hawalli Theater (part of the public schools design developed for Kuwait in the late 1960s by Alfred Roth), which is maintained and was let to us and by local theatre company SABAB.

![]()

A photograph from 1970 of the Kuwait National Museum under construction. Courtesy of Al Qabas Newspaper Archive.

SA | At the symposium you mentioned a few buildings that were recently demolished. There was a particularly beautiful one, I think it was by the sea…

AF | The building of commerce? It was absolutely flattened… it was really well built too. We mentioned it at the talk.

SA | Yeah, that’s the one.

AF | I’ve thought about it at length, about the attitude we have towards the built environment in Kuwait. Ultimately, we’re nomads and so we have this culture or tradition of trekking. To this day, when people go picnicking in the desert they leave their garbage behind and move on, except we’re now sedentary and our garbage is mostly toxic. When Kuwait was more nomadic, a lot of the stuff disposed of was whatever was left of the sheep, date pits, palm fronds… it was all biodegradable, but now it’s not. And yet the same attitude prevails.

SA | I’ve never thought about that attitude of disposal existing beyond the last fifty years, but when you trace the origins of that nomadic mentality, it makes complete sense where the culture comes from.

AF | Yeah, and we’re long sedentary now – we’re settled.

SA | And that happened over a very short period of time. It’s so crazy to think that our grandparents’ generation lived in the ‘soor’ (old city walls)– that was two generations ago.

AF | It’s a very accelerated process… I think that made us really interested in ways of presenting the project beyond the pavilion. Going back to the structure of the project, we took quite a risk assembling things the way we did… Most of the other participating countries worked more conventionally; hired a curator, a contractor and commissioned an architect to design [something] – [a design I felt had] very little connection with issues taking place at [the] ground level. Meanwhile for us it was about fieldwork, doing something locally, using this project as an opportunity to bring together a group of people living and working in Kuwait to think and try and change the way things operate in the country. [It was] only then [that we could] think about how we were going to represent our work in Venice. The project was comprised of various things; a pavilion, a joint installation, ongoing research and a film that we are still working on.

![]()

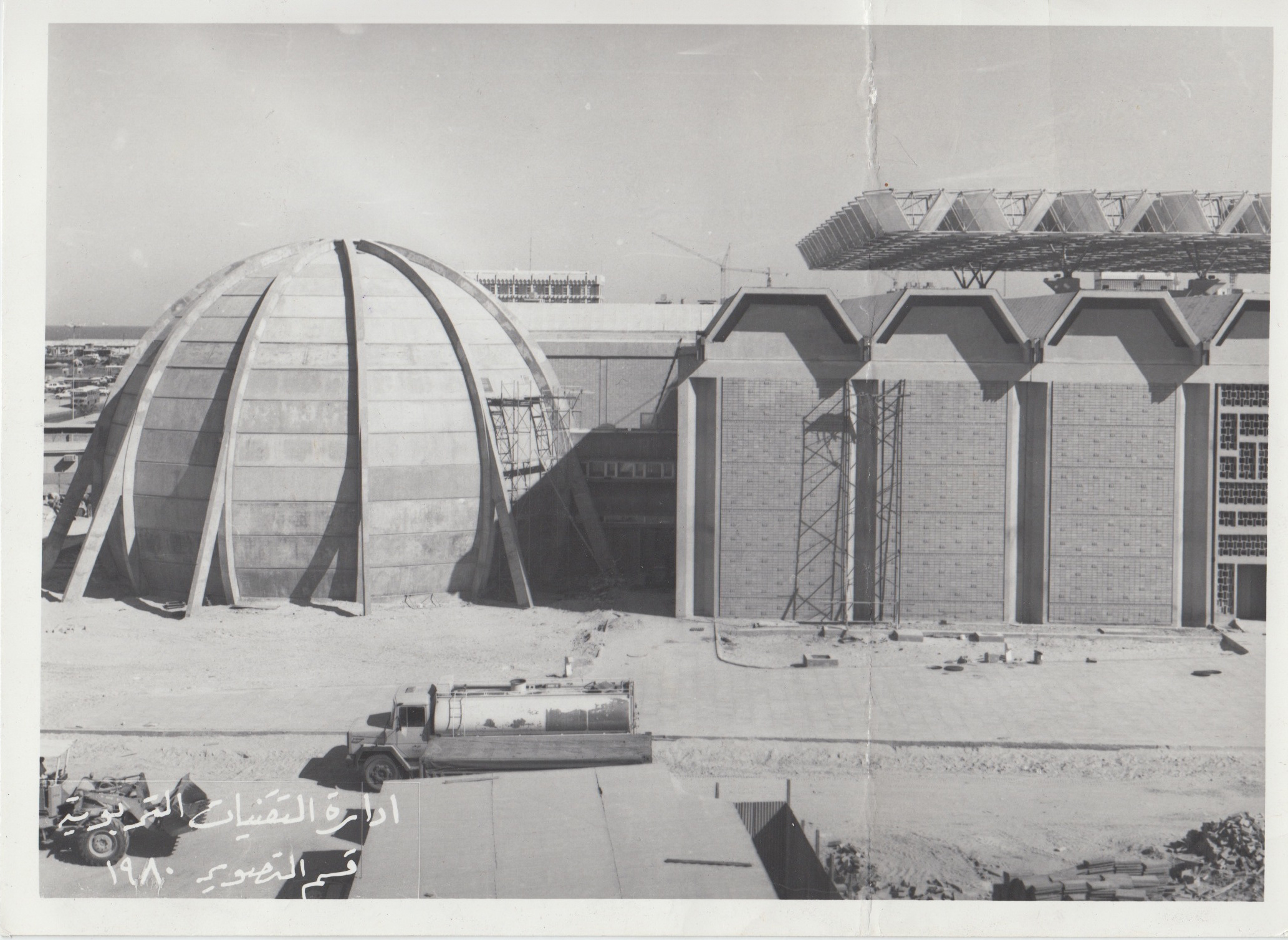

An image of the Kuwait National Museum captured in 1980. In it, the Planetarium and Building IV, Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow. Courtesy of Al Qabas Newspaper Archive.

When I first shared my plans for the project with the NCCAL and explained, it’s a pavilion, it’s a drinking fountain, it’s a publication, it’s ongoing research, and it’s a movie, their reaction was ‘mala salfa’ (there’s no point – regarding the movie). To which I responded, “actually, it has everything to do with the pavilion.” It was about bringing back the pavilion, not through documentation but as something else. The idea of compressed urbanism as it happened in Kuwait, resonates with film as a format. Film is about compressing time, representing time in an hour if you’re doing a feature film or 30 minutes if you’re doing a short. It just felt like the perfect thing to do. And so the research team was divided into a publication team, a script-writing team, and a fabrication team. The fabrication team was in charge of the upshot of the exhibition although it wasn’t really an exhibition in the sense that were weren’t ‘displaying’ anything. It was more an immersive space, a stage, or a set for the film. It was a strategic decision to turn the pavilion into an immersive space-set for a film since we knew we’d have a hard time shipping thing from Kuwait. Bureaucracy in Kuwait is bogus!

![]()

![]()

Views of the Pavilion of Kuwait installation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Courtesy Alia Farid.

[I’ve been told by many people that] experiencing the pavilion felt unsettling. If anything, it faithfully mirrors the current state/condition of the KNM. For others it had an opposite effect. After feeling saturated from walking through the culture-jammed pavilions packed with information and images, arriving at the Pavilion of Kuwait felt like being at a resting stop– a caravansary of sorts with camel-saddle inspired columns… unfinished, dreamy and delightful, albeit ‘unrealised’ in some way. It’s exactly like walking into the KNM and noticing an effort that was abandoned. In fact, the entire project is about rescuing these attempts and continuing the work. Muneera, the story [that] our movie is based on, was written in 1929 and published in a magazine that only ran for two years. The English translation, done by researcher Noura Al Sager, is on our website. Muneera is a simple story, it signals the beginning of a literary movement. Our idea was to rescue some of these literary and artistic activities and remind ourselves of an attitude that is discontinued… because of fear of idolatry and secularism, greed, bureaucracy, war… who knows?

![]()

Images of the drinking fountain joint installation between the Kuwait and Nordic Pavilions, in front of the Nordic Pavilion (Giardini). Sabil (pronounced sa-beel) refers to water donated to a community. Nowadays, sabils are most usually public water fountains, and family members can donate one in the name of a deceased. In the past when water was scarce, sabils served water to travellers and passersby for drinking, ablution, and animal feeding. Although no longer difficult to transport nor in short supply, water in the tradition of sabils still exist in Kuwait, where the fountains have taken on local modernist water-themed designs – such as VBB’s Water Towers and Malene Bjorn’s Kuwait Towers. Courtesy of Alia Farid.

SA | Could you tell me more about the drinking foundations arrangement with the Nordic Pavilion?

AF | The drinking fountain was a charitable donation; it functioned the same way it does here in Kuwait (supplying water to passersby). We set a public drinking fountain in front of Nordic Pavilion in the shape of Swedish architect Süne Lindstrom’s famous Kuwaiti Water towers and had the State of Kuwait pay the water bill. So instead of purchasing bottled water at the Biennale, visitors were able to use the Kuwaiti drinking fountain. After the 14th International Exhibition was over, our drinking fountain was relocated and installed permanently in a public park in Treviso, where it still supplies water to the public.

Acquiring Modernity is Kuwait's participation in the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale de Venezia. Read the press release, explore the repository, or download the research team's publication to learn about the 2014 Pavilion of Kuwait and aspirations to transcends the limits and duration of its installation. Acquiring Modernity was made possible thanks to the tripartite support of the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, the Ministry of State for Youth Affairs, and United Real Estate Company. A recording of the Acquiring Modernity Symposium can be viewed here.

Together, the team produced a volume of essays and photographs regarding the nation’s history of modernisation; a short film entitled Muneera based on the story by Khaled Mohammed Al-Faraj; a collaboration with the Nordic Pavilion to install a drinking fountain (sabil) in Venice, emblematic of Kuwait’s relationship with Danish architecture; lectures and talks regarding the work and research; as well as the actual pavilion itself. The combined efforts of the team resulted in a comprehensive and unprecedented amount of research and critique of architecture, modernity, affluence, and cultural space in Kuwait.

I had the opportunity to attend the Acquiring Modernity Symposium at the National Library of Kuwait last December, in which Alia and fellow team members Dana Aljouder, Aisha Al Sager, Sara Saragoça, and Hassan Hayat spoke on demolition, preservation, public space, and identity. I spoke with Alia, a Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican visual artist who works at the intersections of art and architecture, about the experience working at the Biennale, her thoughts on architecture and local action in Kuwait, and bringing our famous blue and white water fountains to Venice.

AF | The overarching theme and title for the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia was Absorbing Modernity. It was a call asking all participating countries to consider how modernity affected local culture, and for the first time in the history of the architecture biennale the exhibition was being envisaged as a retrospective. Up until 2014 when Rem Koolhaas became director, the biennale had been about representing and highlighting current and future work of prominent or promising architects, but never about looking back. It had never taken this kind of historiographic format/approach. I think everyone was really excited about this. For us in Kuwait, it meant an opportunity to carefully think about what happened to a reverence once held for architecture, and why the city today is the way it is. It’s something a lot of people in the field ask and think about, like ‘shi’salfah’ (what’s the deal)? [laughs]. Where did we go wrong? And so this was a really good occasion to go back and really think about architecture – and the future of architecture – in Kuwait.

Coming from the Heritage and Restoration Department of the National Council for Culture, Arts & Letters (NCCAL), Kuwait’s government cultural organisation, it felt important to align the interests of the biennale with the work being done in the department. Let me explain: the department I was working for is in charge of preserving, restoring, and maintaining buildings of cultural and historical significance in Kuwait. They’re mostly concerned with pre-oil structures, i.e. mud-buildings. There aren’t a lot of these left in Kuwait, but the ones that are still standing are the ones the department is primarily “working” to preserve. The NCCAL has a dated and warped idea about conservation – it’s a common opinion. In a way, our project was not just about rethinking how architecture should be protected in Kuwait, but also about the selection of works preserved and ideologically what they imply. The project became about the future of architectural heritage and encouraging the NCCAL to include modernist architecture and vernacular structures as national monuments, such as the Al Khudhur Shrine on Failaka Island, which has been demolished twice because of sectarian disputes. Why should places like Bayt Dickson be preserved, and not the Al Khudhur Shrine? And why is the Kuwait National Museum (KNM) (Michel Écochard’s masterpiece) adulterated beyond recognition, same with Arne Jacobsen’s Central Bank design?

Tareq Sayed Rajab, the first appointed Director of the Department of Antiquities and Museums of Kuwait (1957) with a group of foreign journalists and archaeologists at the site of the Al Khudhur Shrine on Failaka Island. Courtesy of Tareq and Jehan Sayed Rajab.

SA | I found the subsections for the KNM to be really cool – the ‘Man of Kuwait’, ‘The Future of Kuwait’… could you elaborate on that?

AF | We decided to focus our participation on the KNM, and through its envisaged programme, expand on different subjects related to architecture and urbanism in the country. ‘Land of Kuwait’, ‘Man of Kuwait’, ‘Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow’– these are some of the themes the architect suggested to help the client’s imagination when thinking about possible exhibitions for the museum. Let [me] backtrack for a minute: the KNM compound is made up of four buildings. When the architect arrived in the 1960s to meet his clients (the Ministry of Education at the time) and ask what they planned on exhibiting, he quickly understood that no one knew. The architect then put forward a programme, supplying a headline-theme for each of the four buildings and the planetarium. He described the museum not as a space for the passive viewing of objects, but rather as a cultural space alive with objects and activity. In correlation with each of these headlines, we then organised our research.

Axonometric drawing of the Kuwait National Museum by architect Michel Écochard. Courtesy of the Aga Khan Foundation.

[Starting] in October 2013, we met every Saturday until our departure for Venice. We were a group of 22, each bringing information that we found from all over the place: family archives, the basement of the KNM, the Al Qabas Newspaper Archive, archives in London, Paris, Copenhagen, Cambridge… The headlines became a helpful way of structuring things. And because the KNM is managed by the NCCAL, the hope was that by focusing our participation on the museum, we’d be able to reactivate the space and get it into healthy, operating condition. Meanwhile, we worked out of the Hawalli Theater (part of the public schools design developed for Kuwait in the late 1960s by Alfred Roth), which is maintained and was let to us and by local theatre company SABAB.

A photograph from 1970 of the Kuwait National Museum under construction. Courtesy of Al Qabas Newspaper Archive.

SA | At the symposium you mentioned a few buildings that were recently demolished. There was a particularly beautiful one, I think it was by the sea…

AF | The building of commerce? It was absolutely flattened… it was really well built too. We mentioned it at the talk.

SA | Yeah, that’s the one.

AF | I’ve thought about it at length, about the attitude we have towards the built environment in Kuwait. Ultimately, we’re nomads and so we have this culture or tradition of trekking. To this day, when people go picnicking in the desert they leave their garbage behind and move on, except we’re now sedentary and our garbage is mostly toxic. When Kuwait was more nomadic, a lot of the stuff disposed of was whatever was left of the sheep, date pits, palm fronds… it was all biodegradable, but now it’s not. And yet the same attitude prevails.

SA | I’ve never thought about that attitude of disposal existing beyond the last fifty years, but when you trace the origins of that nomadic mentality, it makes complete sense where the culture comes from.

AF | Yeah, and we’re long sedentary now – we’re settled.

SA | And that happened over a very short period of time. It’s so crazy to think that our grandparents’ generation lived in the ‘soor’ (old city walls)– that was two generations ago.

AF | It’s a very accelerated process… I think that made us really interested in ways of presenting the project beyond the pavilion. Going back to the structure of the project, we took quite a risk assembling things the way we did… Most of the other participating countries worked more conventionally; hired a curator, a contractor and commissioned an architect to design [something] – [a design I felt had] very little connection with issues taking place at [the] ground level. Meanwhile for us it was about fieldwork, doing something locally, using this project as an opportunity to bring together a group of people living and working in Kuwait to think and try and change the way things operate in the country. [It was] only then [that we could] think about how we were going to represent our work in Venice. The project was comprised of various things; a pavilion, a joint installation, ongoing research and a film that we are still working on.

An image of the Kuwait National Museum captured in 1980. In it, the Planetarium and Building IV, Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow. Courtesy of Al Qabas Newspaper Archive.

When I first shared my plans for the project with the NCCAL and explained, it’s a pavilion, it’s a drinking fountain, it’s a publication, it’s ongoing research, and it’s a movie, their reaction was ‘mala salfa’ (there’s no point – regarding the movie). To which I responded, “actually, it has everything to do with the pavilion.” It was about bringing back the pavilion, not through documentation but as something else. The idea of compressed urbanism as it happened in Kuwait, resonates with film as a format. Film is about compressing time, representing time in an hour if you’re doing a feature film or 30 minutes if you’re doing a short. It just felt like the perfect thing to do. And so the research team was divided into a publication team, a script-writing team, and a fabrication team. The fabrication team was in charge of the upshot of the exhibition although it wasn’t really an exhibition in the sense that were weren’t ‘displaying’ anything. It was more an immersive space, a stage, or a set for the film. It was a strategic decision to turn the pavilion into an immersive space-set for a film since we knew we’d have a hard time shipping thing from Kuwait. Bureaucracy in Kuwait is bogus!

Views of the Pavilion of Kuwait installation at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia. Courtesy Alia Farid.

[I’ve been told by many people that] experiencing the pavilion felt unsettling. If anything, it faithfully mirrors the current state/condition of the KNM. For others it had an opposite effect. After feeling saturated from walking through the culture-jammed pavilions packed with information and images, arriving at the Pavilion of Kuwait felt like being at a resting stop– a caravansary of sorts with camel-saddle inspired columns… unfinished, dreamy and delightful, albeit ‘unrealised’ in some way. It’s exactly like walking into the KNM and noticing an effort that was abandoned. In fact, the entire project is about rescuing these attempts and continuing the work. Muneera, the story [that] our movie is based on, was written in 1929 and published in a magazine that only ran for two years. The English translation, done by researcher Noura Al Sager, is on our website. Muneera is a simple story, it signals the beginning of a literary movement. Our idea was to rescue some of these literary and artistic activities and remind ourselves of an attitude that is discontinued… because of fear of idolatry and secularism, greed, bureaucracy, war… who knows?

Images of the drinking fountain joint installation between the Kuwait and Nordic Pavilions, in front of the Nordic Pavilion (Giardini). Sabil (pronounced sa-beel) refers to water donated to a community. Nowadays, sabils are most usually public water fountains, and family members can donate one in the name of a deceased. In the past when water was scarce, sabils served water to travellers and passersby for drinking, ablution, and animal feeding. Although no longer difficult to transport nor in short supply, water in the tradition of sabils still exist in Kuwait, where the fountains have taken on local modernist water-themed designs – such as VBB’s Water Towers and Malene Bjorn’s Kuwait Towers. Courtesy of Alia Farid.

SA | Could you tell me more about the drinking foundations arrangement with the Nordic Pavilion?

AF | The drinking fountain was a charitable donation; it functioned the same way it does here in Kuwait (supplying water to passersby). We set a public drinking fountain in front of Nordic Pavilion in the shape of Swedish architect Süne Lindstrom’s famous Kuwaiti Water towers and had the State of Kuwait pay the water bill. So instead of purchasing bottled water at the Biennale, visitors were able to use the Kuwaiti drinking fountain. After the 14th International Exhibition was over, our drinking fountain was relocated and installed permanently in a public park in Treviso, where it still supplies water to the public.

Acquiring Modernity is Kuwait's participation in the 14th International Architecture Exhibition of la Biennale de Venezia. Read the press release, explore the repository, or download the research team's publication to learn about the 2014 Pavilion of Kuwait and aspirations to transcends the limits and duration of its installation. Acquiring Modernity was made possible thanks to the tripartite support of the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, the Ministry of State for Youth Affairs, and United Real Estate Company. A recording of the Acquiring Modernity Symposium can be viewed here.

Shoag

Al-Adsani recently graduated with a degree in English literature and is

looking to master in development studies this coming year.